A Brief History of Perforated Metal

A brief history of perforated metal.

The history of perforated metal spans several millennia. Its usage has varied from decorative to functional — very often at the same time. It has appeared in many cultures and for many purposes throughout time, from ancient arts and crafts, to warfare technology, to industrial filtration and sorting mechanisms. Today, perforated metal has returned as a highly decorative and expressive artistic medium.

Note: In 2017, Zahner introduced a new system for designing and procuring custom picture perforated imagery. Design your own picture perf at ImageWall.com — and make history with perforated metal.

EARLY HISTORY — THE ROOTS OF PERFORATION

The modern English word “perforate” comes from the Latin “perforo” which means to “bore”, “pierce-through” or “penetrate.” Perforated materials are typically made by piercing using some sort of punch or cutting technology.

In many of the earliest examples of perforated metal, a rudimentary technique was used to punch into a material. This is evidenced by the barbed edges, which indicate a far more violent approach than the machine-smooth perforated metal you see today. It’s fitting that many older examples of perforated metal were related to warfare usage. However, there are many examples of perforation which precede it.

Before there was perforated metal, early humans and hominids created perforated materials to serve a decorative or domestic purpose, from ornamental shells used in necklaces, tools used for cheese-making, or even some of the earliest marks made by primitive humans in the Paleolithic era—deep perforations or “cupules” made in stone thought to indicate artistic or symbolic thought.

Islamabad cupules, Pakistan, 290,000-700,000 BCE.

Photo courtesy Petrobiology.

Cupules in Biella, Italy, 290,000-700,000 BCE.

Photo courtesy Alberto Vaudagna.

Cupules are a fascinating example of early perforation marks made on stone from several-hundred thousand years ago. Although we don’t know exactly what purpose these ancient marks served, we do know that the effort required to make these with the available tools was significant.

Depending on the depth, each cupule was achieved through thousands of blows to the hard stone surface, and one researcher estimates up to 21,000 blows — how far we have come! Today a modern punch produces multiple perforations per second.

Beginnings of PERFORATED METAL — EARLY Civilization

Early civilization would lead to the discovery of various metals and subsequent forming into domestic, art, and warfare objects. As a durable material, it appeared in many aspects of life, serving both decorative and functional purposes.

In many civilizations, including Asian, Native American, African, and European, their respective cultures’ coinage made use of a perforation or hole at the coin’s center. These coins vary in material, including not only metals, but also stone and marble. While many have speculated that the holes allowed the coins to be strung together, it is just as likely that placing a hole in the coin reduced the amount of metal used to make the coin, saving resources.

The emergence of perforated metal, and its densely patterned areas, wouldn’t appear until the age of modern hand-to-hand combat. These tighter perforations allowed for greater protective coverage while providing breathability and visibility for its occupants. In the helmets below, we can see the Sumerian culture’s transition from stone to metal. Perforations in the helmets were used to attach cloth armaments. Thought to be decorative, the same design was first used on stone and then gold helmets (the two helmets on the left were made within a hundred years of each other).

Stone helmet, Sumeria; 2500 BCE.

Photograph ©Sumerian Shakespeare.

Gold Helmet, Sumeria; 2600 BCE.

Photograph © Sumerian Shakespeare.

Bronze helmet, Rome; 500-525 CE.

PHOTOGRAPH © JASTRO.

Steel helmet, Milan; C. 1400-1410 CE.

PHOTOGRAPH © SANDSTEIN.

Coins and historic sketches of coined currency with holes.

Imagery courtesy of Wikipedia Commons.

Ecuadorian metal object with three holes, from Huigra

PHOTOGRAPH © Wellcome Images.

15TH CENTURY MEDIEVAL CUIRASS USED IN SPECIAL TOURNAMENTS AND FESTIVALS, PERFORATED FOR ITS LIGHTER WEIGHT AND VENTILATION.

Rendering from the Book of Tournaments René d’Anjou.

Perforated metal was used in helmets as a way of providing protection of the eyes and mouth while allowing for full disguise of the face — all the while providing great visibility for the wearer. Militaries capitalized on the use of perforation, creating intimidating aesthetics without worrying about whether the infantry would be able to breathe and see through their helmets.

Other examples of perforated military armaments, such as the cuirass plate armor below, were perforated to provide ventilation in specialized tournaments — think of it as medieval hockey armor.

Industrial revolutions — The beginning of Uniform Sheet Metal

Up until the modern era, perforated metal was largely produced on hand-flattened metal. From its earliest examples, metals were hammered flat using stones and other tools. Handcrafted source material meant that perforated processes (and any other processes) were likewise handcrafted.

For several millennia, this process didn’t dramatically change, so when the industrial rolling mill was first introduced in 1615 (based on a one-hundred year old design by none other than Leonardo Da Vinci), it would revolutionize the possibilities for further industrialization of metal craftsmanship.

Rendering of Leonardo da Vinci rolling milll, ca. 1515 CE.

Milan, Biblioteca Ambrosiana, Codex Atlanticus.

After the first industrial sheet metal began appearing, a world of possibility emerged for metalworking. Uniform sheet metal was like a blank canvas — a new medium to be explored. Shearing, forming, folding — and then punching, perforating, laser/waterjet-cutting — these processes could only emerge from the uniformity that modern sheet metal offers.

The emergence of Machine perforated metal

Over the next few hundred years, advances in the production of sheet metal would set the stage for machine-punched metal. The first machines for perforating metal occurred in the mid-to-late-1800s. At that time, woven wire and cloth were used to filter oil, and these wire filters would wear down due to abrasion. Eli Hendrick, an American industrialist, began drilling holes in thicker plate which would endure, but he quickly realized that he would need a machine that could automatically punch holes simultaneously. This metal-punching machine served as a prototype from which the modern perforating punch would emerge.

Similar innovations were occurring across the United States (and the world) during these years to solve similar problems. One company developed a perforated metal process to refine and sort coal. In the United Kingdom, an early version of expanded metal was developed in the 1880’s, which would introduce the first zero-waste method of creating perforations in metal.

THE RE-EMERGENCE OF PATTERN

As the industrial use of perforated metal began to appear, so too did perforated metal patterns, made by varying, rotating, and spacing custom perforated machinery. In addition, by the late-1800’s, industrial casting and expanded metal began to offer unique opportunities to create perforated metal aesthetics with wildly custom options.

Cast aluminum perforations, Monadnock Building.

Photo courtesy Historic American Buildings Survey.

Advertisement for architectural grilles. c. 1920.

Photo courtesy Urban Remains.

Advertisement for custom perforated metal, c. 1905.

Architect and Engineer.

The Innovation of Digital Perforated “Pixels”

In the early 2000’s, perforated metal entered a new phase of its history, and has since proliferated through the use of digital technologies to develop pattern and image-based perforation.

Zahner played a significant role in the innovation of custom perforated metal. Working for Herzog & de Meuron on the de Young Museum in San Francisco, Zahner was challenged with the custom perforation of 1.7 million individual punched holes throughout the building’s nearly 8000 skin panels. To achieve this, Zahner developed and patented a software system with Eric Wilhelm to translate images into “G” code of “pixellated” imagery. Working with the architect, this system was used to iterate various designs. Once finalized, the digital code was translated to operate machine punches.

ly example of image-based perforated metal: de Young Museum (Left) and original source imagery (Right).

Photo © A. Zahner Company.

The de Young Museum in California, early example of digitally defined picture perforated metal.

Photo © A. Zahner Company.

The re-emergence of functionality in perforated metal

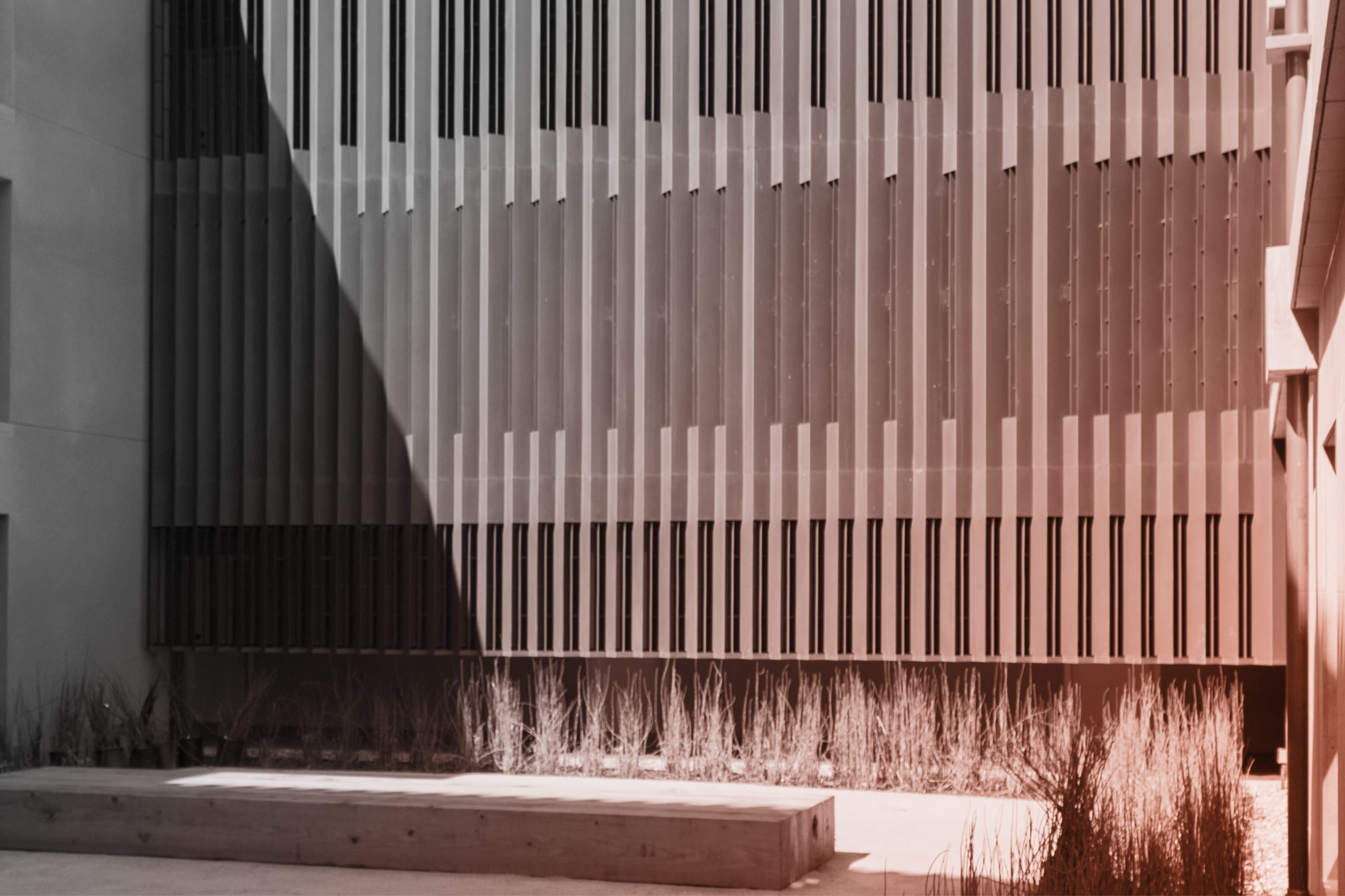

The innovation of picture perforation led to many possibilities in aesthetics. In the next ten years, from 2005 to 2015, a new body of research began to unfold in facade technologies. By using perforated metal as a double-skin on the exterior of a building’s facade, owners realized that they could potentially reduce energy usage. Combined with durable metal systems with long-life spans, the potential for enormous energy cost savings emerged.

Double-skin perforated metal facades have shown that the use of perforated metal sheets as a secondary layer in a buildings’ facade can result in energy savings for heating, cooling, ventilation, and lighting energy consumption.

Contemporary architects are using perforated metal to express visual aesthetics, while lowering the cost of a building’s energy consumption. In 2017, Cornell will open its Roosevelt Island campus with Bloomberg Center, a Net-zero building designed by Morphosis. The building is slated to have a net-zero or net-positive energy usage, and the building’s facade plays a role in reducing the building’s energy use.

Cornell Tech’s Bloomberg Center, photographed during construction in 2016.

Photo © A. Zahner Company.

Detail of the louver-perforated facade for Cornell Tech’s Bloomberg Center.

Photo © A. Zahner Company.

The creation and use of perforated metal has come a long way; as systems continue to evolve, who knows what might come next!

LEARN MORE ABOUT Creating Perforated metal

Did you like this post? Sign up for the Zahner mailing list to learn more about what we offer for architects, designers, and artists. To get started with a project which integrates custom perforated metal, contact a member of the Zahner sales team, or try our image-to-perforation software at ImageWall.

ABOUT A. ZAHNER COMPANY

Since 1897, across four generations, the family-owned business of A. Zahner Company has produced highly crafted architectural metalwork for artists and architects around the globe. Throughout the company’s history, employees at Zahner have developed advanced metal surfaces and systems for both functional and ornamental architectural forms.

Zahner’s mission is to surpass the expectations of clients by expanding the boundaries of high-quality metal and glass used in art and architecture. The company pushes the levels of technology while providing a worthwhile, challenging, and safe environment for employees and associates.

References:

- Ancient Rome; Carlisse, David, Mar 18, 2014

- Studies in Ancient Technology, Volume 1. Forbes, Robert James.

- The King of Kish, Sumerian Shakespeare, Inim Shukur, July 12, 2012

- Perforated Metals Handbook, Industrial Perforaters Association

- A Short History of Sheet Metal Metalworking Magazine.

- Cupules – The oldest known style of Rock Art, Sandeep Ahirwar 2017-01-25

- Energy assessment and optimization of perforated metal sheet double skin façades through Design Builder, Ilzarbe, Buruaga, Roji, & Pelaz, December 2015.

PHOTO © A. ZAHNER COMPANY.

PHOTO © A. ZAHNER COMPANY.

PHOTO © A. ZAHNER COMPANY.

PHOTO © A. ZAHNER COMPANY.

Photo ©

Photo ©

PHOTO ©️ Parrish Ruiz de Velasco (parrch.com)

PHOTO ©️ Parrish Ruiz de Velasco (parrch.com)

Ɱ, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license, edited.

Ɱ, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license, edited.