Get Inspiration, Delivered.

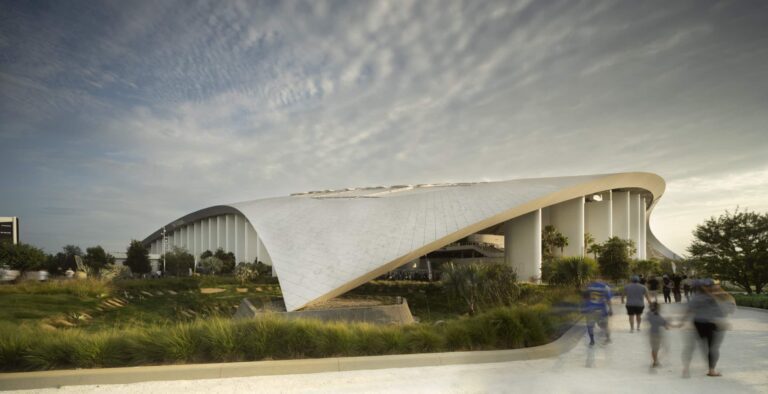

Join our newsletter and get inspiring projects, educational resources, and other cool metal stuff, straight to your inbox.

The surfacing of copper and copper alloys is an art form in itself. From the beginning, the mill undertakes a process to produce the finish on copper alloys that demonstrates care for the intrinsic beauty of this metal.

It seems almost a shame to develop a patina over such a surface. However, once the patinuer (an artisan who applies the finish) begins, the metal comes alive with color. The subtle detail takes form. Colors enhance the contrasting shadows and a new richness takes shape.

This is the beauty of copper and copper alloys. Its thermodynamic character offers a stability that welcomes the arrival of new elements. While its ductile nature encourages the creation of surprising textures.

PHOTO © A. ZAHNER COMPANY.

Mill Surface to Mechanical Finish

The mill produces a clean, smooth surface on copper and copper alloys. Cold-rolled copper products—including sheets, coils, rods, bars, and some plates—are produced with an “as fabricated” finish. It has good reflectivity but lacks the refinement of an applied mechanical surface.

For copper alloys, this finish is usually smooth, clear, and reflective. Even tubing produced at the mill is clean and free of marks and scratches. The beauty and luster of the metal demand that it be handled with care.

Typically, copper alloys are finished further at a polishing or fabrication facility. Mechanical finishes like satin polishing, mirror polishing, and on occasion, glass bead blasting, are often used on copper and copper alloys when the design seeks a more refined surface.

In addition, embossing and custom hammering are macro surface deformations used on some softer alloys to add stiffness while enhancing appearance.

PHOTO © FRANCISCO & KATE.

PHOTO © FRANCISCO & KATE.

Satin and Mirror Finishes

The mechanical processes performed on copper alloys, either as initial finishes for later patination or as final finishes, involve similar techniques to those used on stainless steel and aluminum.

Satin or matte finishes can be achieved through controlled scratching, satin directional finishing with scrubbing pads, aluminum oxide discs, silicon carbide discs, and glass bead blasting. These methods all produce a degree of diffuse light as it is reflected from the copper surface.

For a mirror finish, polishing and buffing operations involve a step-down in rouges. Copper alloys—except the aluminum brasses—take well to mechanical polishing because of the relative softness of the surface.

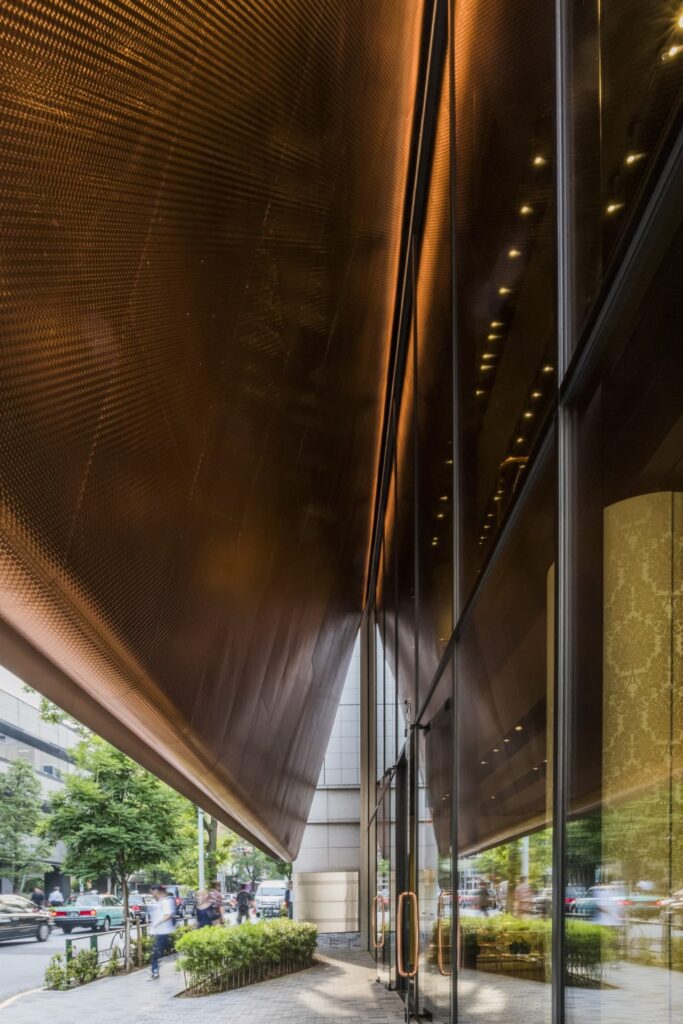

Polishing and buffing can develop bright, mirror-like reflective surfaces on copper and copper alloys. Consider the polished copper interior walls at the Miu Miu Aoyama, designed by Herzog & de Meuron. The reflectivity is specular but not overwhelming. The in-and-out bumps on the surface mute the reflectivity, similar to how frit alters light passing through glass.

Photo by Tex Jernigan | ARKO

Photo by Tex Jernigan | ARKO

Photo by Tex Jernigan | ARKO

Statuary Finishes for Darkened, Metallic Beauty

Statuary finishes are common chemical finishes used on copper and copper alloys, particularly brass alloys. These finishes are semi-transparent and when properly applied, give rise to a darkened, metallic beauty.

Working with the Libeskind design team, a very light statuary finish was created to achieve the desired appearance for the Ohio Holocaust and Liberators Memorial. As light reflects off the base metal, it creates a reddish tonal effect that changes slightly depending on the angle of view. This color tone provided sufficient contrast to the lettering on the sculpture.

PHOTO © A. ZAHNER COMPANY.

A darkened statuary finish can also give copper alloys a deep, old bronze appearance. The term “statuary bronze” is associated with this type of finish. The Bowdoin Museum of Art features Zahner-fabricated naval brass with a custom bronze patina.

Several other color variations are available in the statuary finish category. One that has found use on several architectural surfaces is the premium Zahner finish, Dirty Penny™. We’ll explore this preweathered copper patina surface in the next installment of this series.

Photo © Lisa Logan

A Rainbow Of Copper Patinas

In Italian, the term patina means a thin layer of deposit on the surface of an object. Today the term has taken on a more expansive definition and means any desirable color tone on the surface of any metal. From black to red to green to gold, let’s explore the colorful possibilities of patinas.

Black Patinas

Black patinas have been used on copper alloys from the early days, allowing artisans to highlight and provide contrast in bronze and copper fabrications. These artisans would either etch into the blackened plate so that the metal could show through or reverse the process, leaving the etched portion black while polishing the balance of the artwork.

PHOTO © DANIEL HOLTON.

PHOTO © DANIEL HOLTON.

Zahner provided the interior and exterior copper metalwork with a preweathered patina for The Robert Hoag Rawlings Public Library in Pueblo, Colorado. The building’s dark patinated copper tones blend it masterfully into its natural regional landscape.

Black patinas can be found in both exterior and interior use. This durable black finish absorbs solar radiation and can get quite warm. A roof clad in blackened copper patina will shed snow and ice more rapidly as it heats quickly in the sun.

If the metal is placed where it can be touched or if handling is extensive, Zahner suggests a protective coating for the surface.

Photo © A. Zahner Co.

Red Patinas

Red is the color of cuprous oxide, so one would think this would be a common and achievable color. However, it is a difficult color to produce in copper alloys. This complex patina has questionable stability unless the metal is coated and sealed from the environment.

The red finish, when achieved, is rich and beautiful. It will change over time and darken, in sometimes beautiful ways, if not protected with a clear coating.

Natural and Artificial Green Patinas

Natural green copper patinas form over time via the interaction of moisture, pollution, chlorides, and carbon dioxide on the surface of copper and copper alloys.

The rich green color on a copper roof and the oxidation of a bronze sculpture in a fountain are both manifestations of the natural progression of surface decay. Although the results are similar, the consequences are far different.

The copper roof is allowed to oxidize and grow a beautiful green tone that resists further oxidation, as shown on the Berlin Cathedral or the 1909 spire on the Nikolaj Contemporary Art Center. The sculpture, on the other hand, is undergoing surface changes that are irreversible and can damage the original design intention.

However, one only has to look at the ancient sculptures that have been residing under the sea for centuries to observe that they are still intact and recognizable. When some maintenance is performed, bronze sculptures can last centuries and appear as if they were cast in recent times.

PHOTO @ A. ZAHNER COMPANY

PHOTO @ A. ZAHNER COMPANY

Successful green artificial copper patinas mimic the oxidation occurring in natural exposures at an accelerated pace. They are produced in a concentrated and controlled environment to arrive at a predictable outcome and a specific color tone.

They are a decorative treatment to copper alloy surface, planned chemical reactions on the surface between the copper and chemical compound. There are numerous formulas for creating artificial patinas on copper and copper alloys. Zahner offers Star Blue™, a proprietary preweathered copper surface that we’ll discuss in depth later in this series.

Photo © A. Zahner Company

Additional Patina Colors, Hot and Cold

Colors produced by patinating copper alloys are dependent on the chemicals used (to cause the reaction) and the makeup of the metal at the surface. You can use the same chemistry, temperature, and humidity on two different alloys with two different results.

One can see the various color possibilities and patina characteristics in the following chart:

| Color | Chemical Compound | Difficulty |

| Black | Potassium sulfide Ammonium sulfide Hot sodium hydroxide | Easy to achieve. Chemicals have pungent odors and short shelf lives. There are a number of proprietary mixtures. |

| Brown | Ferric nitrate Potassium sulfide Copper sulfide | Easy to use. Various concentrations. A number of proprietary mixtures. |

| Antiqued | Potassium sulfide | Easy to use. Several proprietary mixtures are available. |

| Green | Copper acetate Copper carbonate Copper nitrate Copper sulfate | Several proprietary mixtures available. Hot and cold versions. Can be layered with potassium sulfide or ferric nitrate solutions to adjust color. |

| Blue green | Copper nitrate Copper chloride | Temperature sensitive. Can be combined with ferric nitrate solutions to adjust color |

| Yellow to orange | Ferric nitrate | Altering the strength can push the color from golden brown to yellow. |

| Red | Ferric nitrate Copper sulfide | This is a hot application. Can be difficult to achieve. |

There are two distinct categories of patination processes: the cold application and the hot application. The cold application process is popular on wrought forms of copper, such as sheet and plate, and can be layered to create different effects.

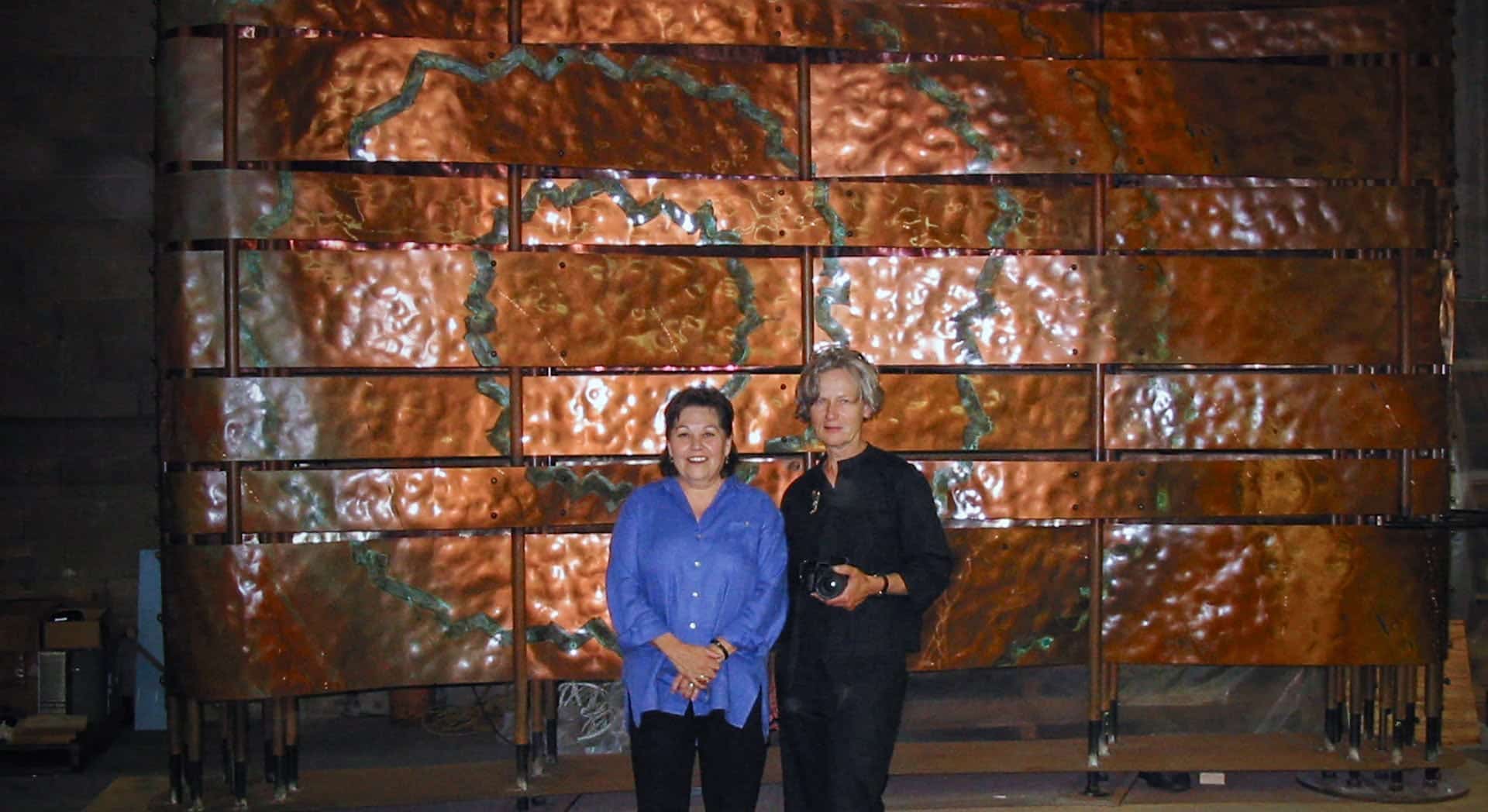

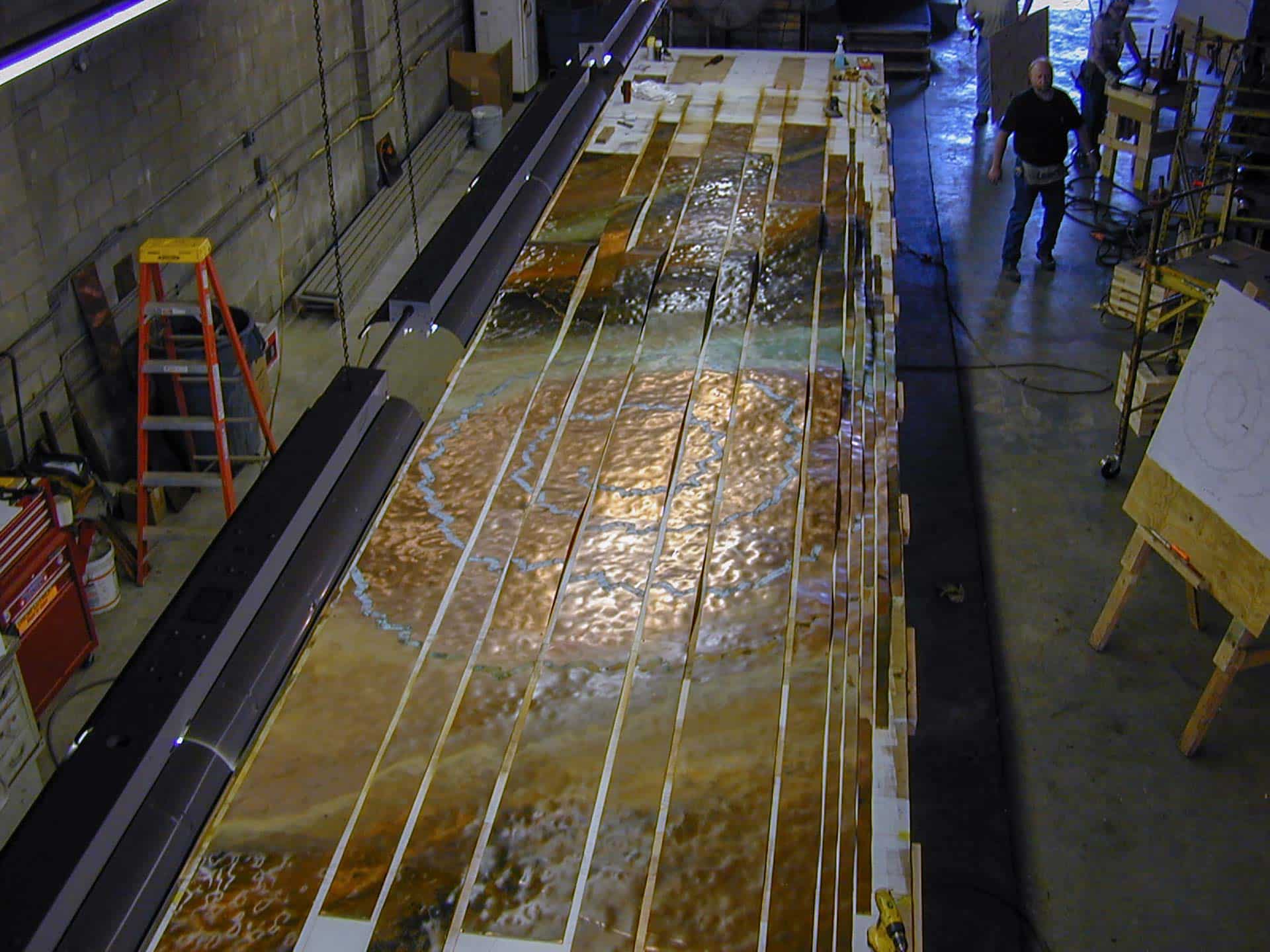

Photo © A. Zahner Company

A cold patina process created the beautiful surfaces on the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian art wall. The layering method was applied to create a mosaic effect.

The hot application process is predominantly used on castings and sculpture due to the potential for warping thinner plates and the ability of thick castings to distribute the heat from the process.

As with the cold patina process, the solutions may be layered as the surface reheats. In the hands of an expert, stippling effects and other artistic techniques can significantly enhance the cast sculpture.

In both processes there is a consistency in how the surface is prepared. A clean surface free of all oils, soil, and water is critical for a successful patina to develop. Starting with a clean surface can often be one of the more difficult steps in the patination process.

PHOTO © A. ZAHNER COMPANY.

PHOTO © A. ZAHNER COMPANY.

PHOTO © A. ZAHNER COMPANY.

Melted Copper Alloy Surfacing

Copper alloys have different melting temperatures, as the constituents that make up the alloys melt at different rates. When the surface heats to the point where the metal reaches its liquidus temperature (the point at which it begins to melt), some components vaporize while others move about in the molten metal on the surface.

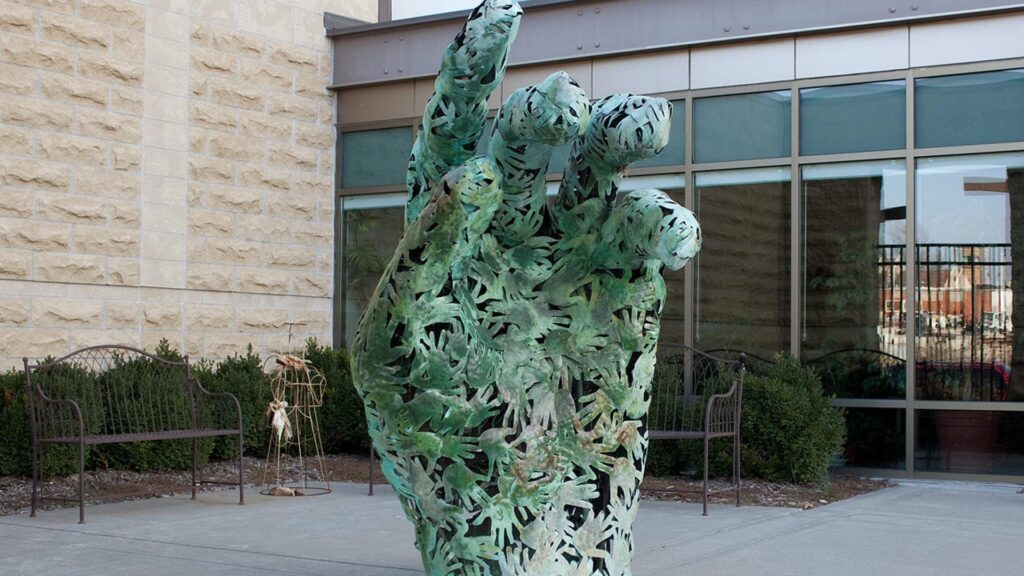

Copper alloys move the heat away quickly. As you blast the surface to increase the temperature, the copper and other components flow. It creates remarkable surface effects. You can see this process in the art piece produced for the 9/11 Memorial in Overland Park, Kansas.

Contemporary Advances in Copper Textures

From earliest times during the discovery of copper, the ability to hammer the metal into shapes and forms was one of the most endearing properties of this special rock. Artistic surface techniques first used by early craftsmen have transformed via modern methods of imparting designs into the malleable surface of copper alloys with startling results.

Recall the interior walls of the Miu Miu Aoyama mentioned earlier in this post. The copper bullnose details, with dense custom perforations and round zig-zag seams, produce breathtaking depth and beauty.

PHOTO © FRANCISCO & KATE.

Repoussé and chasing: The French term “repoussé” means pushing up or out and refers to raising the metal by hammering on the reverse side. “Chasing” is based on the French term chasser, which means to drive or push out. Both are often performed on the same metal sheet to create intricate detail.

Hammered Texture: A step away from the artistic repoussé that utilizes the softness of copper. The metal can be heated and hammered into forms or shapes without ripping or tearing along edges, then oxidized to develop beautiful tonal effects no other material can match.

Embossing: The process of running sheets or coils of thin copper alloy through engraved patterning rolls, which impart the patterns into the copper alloy. Wood grain, leather, and stucco patterns are just a few patterns chosen. An added benefit is that the texture stiffens the copper surface while concealing minor flaws.

CNC Texturing

With the advent of CNC equipment, the ability to shape and form copper alloys has advanced in unique ways. One-of-a-kind textural surfaces are introduced into copper and copper alloy surfaces as remarkable shapes take form.

Other metals can be shaped in a similar fashion, but copper and many of its alloys do not develop excessive local stresses that can warp the surface.

Larger textures are also possible using this equipment. These macro forms in the metal produce shadowing effects that will oxidize at different rates depending on how the condensation remains on the surface.

The surface of the de Young museum’s copper walls illustrates this technique. Here, a series of nine different cone-shaped indentations were pushed inward or outward from the plane of a sheet to develop subtle contrast on the museum’s exterior walls.

This copper facade will, over time, transition from bright golden red to dark brown to black (eventually emerging into earthy greens).

PHOTO © A. ZAHNER COMPANY

Etching and Engraving

Copper and copper alloys can be etched or engraved to produce extensive surface detail. In both processes, the material is selectively removed.

Etching involves the localized chemical dissolution of the metal and usually necessitates the application of a resist to the surface of the metal not to be dissolved.

Engraving removes metal by mechanical means. Selective abrading, machining, waterjet, and laser cutting can engrave the metal’s surface. Fine machining and control of the tool are critical.

During the impressive entrance portal construction for the Museum of the Bible commissioned by artist Larry Kirkland, vertical lines were etched into the thick brass panels. This design choice nods to the original lines produced from individual type blocks used in Gutenberg’s printing technique.

The Future of Copper in Art and Architecture

From the early dawn of the copper age to contemporary life, the ingenuity this metal has produced is astounding. Copper’s high ductility, combined with the seemingly endless potential of its alloys, project it favorably into the next century.

Awareness is building in the field of sustainability and the unique challenges we face moving forward. As our world evolves, so do the materials we work with. A timely understanding of the current experiments and groundbreaking developments is vital when working with copper in art and architecture.

PHOTO © A. ZAHNER COMPANY.

NEXT: Dirty Penny™: Zahner’s Premium Copper Patina Surface With Iridescent Appeal

In our next installment of this series, we’ll explore the stunning architectural surface designed to transform over time.

Read Part 3 in our series: Dirty Penny™: Zahner’s Premium Copper Patina Surface—Coming Soon!

To find out more about using stainless steel and how this material can be used in your next project, contact us for samples, or call +1 (816) 474-8882 to speak with one of our Project Specialists.