Copper Guide Part 1: Copper Alloys—from the Stone Age to Modern Metal Marvels

From ancient Egyptian infrastructure to inspiring art and architecture, copper and its alloys continue to influence our contemporary world.

While many metals have influenced society, not all can claim an entire age in their namesake. From the Sumerians and Chaldeans in Mesopotamia, across Egypt, to present-day Turkey and India, copper has captivated early civilizations dating back to 8000 BC.

The weight and malleable nature of copper was a pivotal discovery because its plasticity was like no other known material. Copper was no ordinary rock—it would not fracture yet yielded to blows and took a different shape.

When the nature of this material (with excellent ductility, high elasticity, and soft edges) was discovered and disseminated by our early ancestors, the Stone Age was over, and the Copper Age was upon civilization.

Let’s explore the fundamentals of copper and its alloys, the pivotal role it plays in modern civilization, and how time itself impacts this intriguing material.

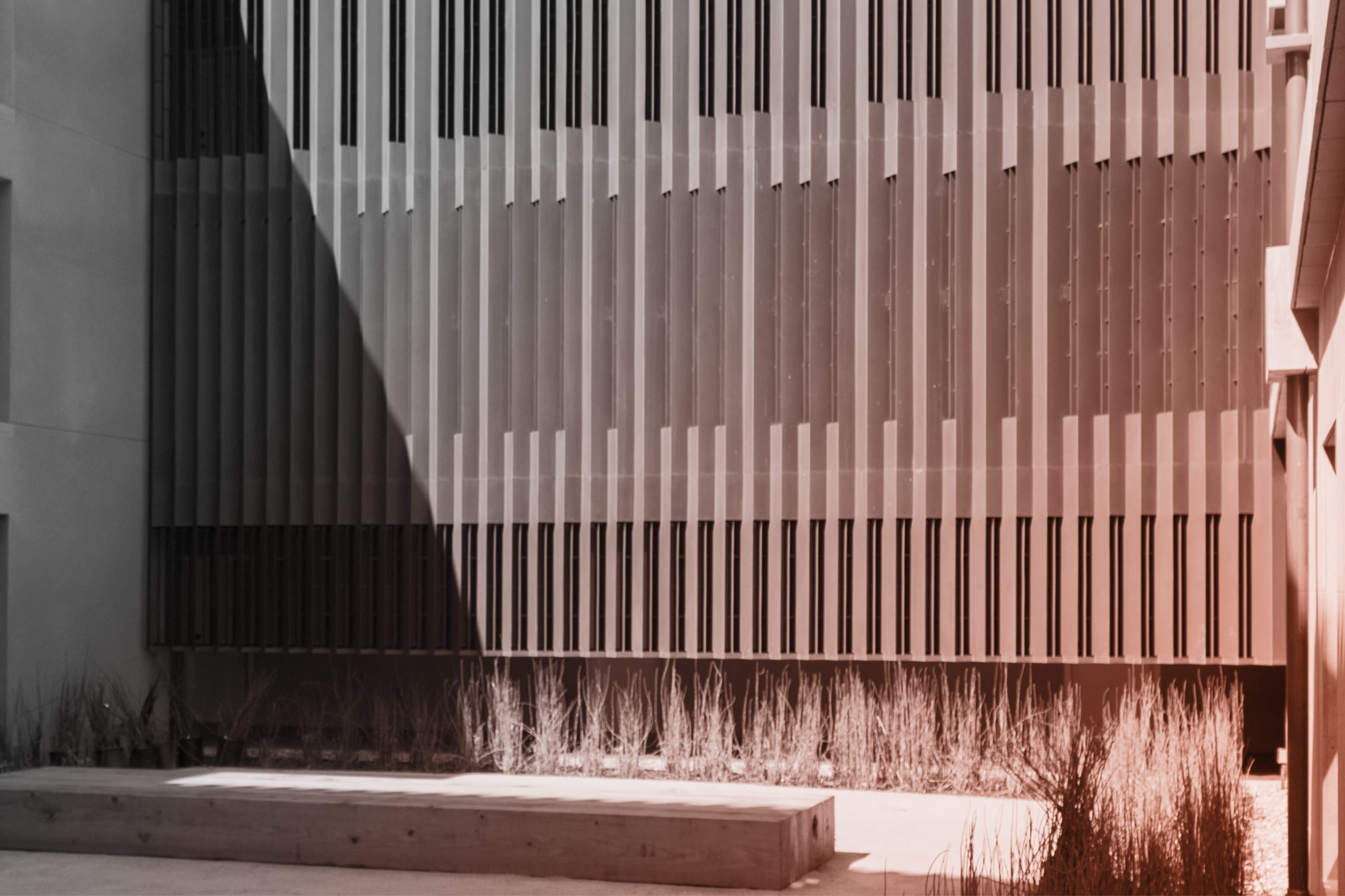

IRVING CONVENTION CENTER SUSTAINABLY DEVELOPED WITH A COPPER EXTERIOR.

PHOTO © A. ZAHNER COMPANY.Copper and its Alloys

Of all the metals, only copper and gold possess colors other than gray or silver in their natural forms. Additional elegant colors and tones take hold when copper combines with different elements (early humans were surely captured by the brightly colored ores of copper, malachite, and azurite).

In its commercially pure state, copper is a soft and malleable metal. However, when alloyed with certain other elements and strengthened by thermal and mechanical means, some alloys approach the strength of steel.

Over time, a vast array of alloys with select properties were created for specific environments and manufacturing processes. That’s the beauty of copper, a metal that has been a cultural mainstay for centuries.

Limitless endeavors were devised, and a vernacular all its own surrounds the metal. Names such as Admiralty Metal, Engravers Brass, Naval Brass, Jewelry Bronze, Gilding Metal, and Cartridge Brass were created by industries to describe a particular alloy (established for a specialized purpose).

Upward view of the Freedom Center copper panels which have patinated to a dark red-brown.

Photo © A. Zahner Company.Elements added to Copper

The following elements are often found in many copper alloys used for art and architecture:

- Zinc – The most common alloying element added to copper. It increases strength and resilience while lending a yellow, golden tone.

- Silicon – Reduces the melting point while increasing fluidity in castings.

- Tin – Improves corrosion resistance and hardness.

- Aluminum – Improves strength and corrosion resistance while adding a yellow-gold tone.

- Manganese – Improves casting properties and enhances the strength of copper.

- Phosphorus – Added in small quantities to deoxidize copper, improve ductility, and increase strength and corrosion resistance.

- Nickel – Improves hardness and strength while enhancing corrosion resistance significantly.

- Silver – Not added as an alloying element, but some traces of silver are found in copper and copper alloys.

Bronze Surface

PHOTO © A. ZAHNER COMPANYBrass Surface

PHOTO © A. ZAHNER COMPANYBeauty, Brass, and Bronze

We often consider copper, brass, and bronze to be completely different metals. In many ways, they are. Brass is the name given to copper alloys with zinc as the major alloying constituent. Bronze is a term used to describe alloys of copper and tin (or copper and silicon).

Both make up a considerable amount of the copper alloys used in art and architecture. Copper alloy C22000 (commonly known as Commercial Bronze) is a popular architectural metal and was chosen for the 18-ft-high bronze panels in the Ohio Holocaust and Liberators Memorial by Daniel Libeskind. Coveted for its soft, golden bronze tone, C22000 can be mirror polished, glass bead blasted, or satin finished.

OHIO STATEHOUSE HOLOCAUST AND LIBERATORS MEMORIAL

Photo © Brad FeinknopfHOLOCAUST AND LIBERATORS MEMORIAL.

Photo © Brad Feinknopf.HOLOCAUST AND LIBERATORS MEMORIAL.

Photo © Brad Feinknopf.HOLOCAUST AND LIBERATORS MEMORIAL.

Photo © Brad Feinknopf.Brasses are valued for their unique, pleasing colors—colors that range from golden bronze to a yellowish-gold hue. Compared to commercially pure copper, zinc increases the strength and stiffness of the copper alloy without having a major effect on corrosion resistance.

In the early twentieth century, nickel silver provided a silvery tone to set alongside brightly polished brass. At the time, these stunning art deco forms represented the modern age—and a sense of opulence that extends to today.

Resisting (or Embracing) Oxygen’s Attraction

Capturing and maintaining the brightly polished surfaces of copper alloys is no easy task. Methods have been employed over the years to eliminate the powerful drive of the single valence electron of copper to combine with oxygen, the combination that results in the tarnish on the surface of copper alloys.

This is not an issue, however, with the aluminum–bronze alloys. The aluminum bronzes C61000 and C61500 are the most corrosive-resistant of the copper alloys. Still, constant polishing and cleaning are necessary to keep most copper alloys appearing bright and golden. They can be coated and waxed to reduce the frequency of the cleaning regimen.

PATINA TRANSITION OVER TIME ON THE DE YOUNG MUSEUM.

PHOTO © A. ZAHNER COMPANY.Enjoying this article? Take a deeper dive with:

Copper, Brass, and Bronze Surfaces: A Guide to Alloys, Finishes, Fabrication, and Maintenance in Architecture and Art (Architectural Metals Series)

By L. William Zahner

Copper, Brass, and Bronze Surfaces, third in Zahner’s Architectural Metals Series, provides a comprehensive and authoritative treatment of copper, brass, and bronze applications in architecture and art. It offers architecture and design professionals the information they need to ensure proper maintenance and fabrication techniques through detailed information and full-color images. It covers everything from the history of the metals and choosing the right alloy, to detailed information on a variety of surface and chemical finishes and corrosion resistance.

The Robert Hoag Rawlings Public Library in Pueblo, Colorado.

PHOTO © DANIEL HOLTON.Exterior roofing and thin copper wall cladding are rarely coated with protective coatings, even if given an artificially induced patina. It is better to allow them to react and change with the environment than to undertake the expensive and somewhat futile endeavor of maintaining their clear coatings.

For example, the de Young museum in Golden Gate Park, San Francisco, has walls and a roof composed of cold rolled copper sheets that are weathering naturally and beautifully.

Copper’s History: Early Infrastructure and Naval Warfare

The ductile nature of copper was a characteristic that man could first use to his advantage in early infrastructure. Copper was hammered thin and used in crude water-piping systems in early Egypt. The Romans used thin plates of copper to clad the roof of structures such as the Pantheon, while artisans familiar with this pliable metal created helmets and shields.

The metal sheathing of Cutty Sark, made from copper alloy.

Photo By Cmglee.The remains of an early-19th century wooden ship.

Photo By Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management Headquarters.Fast forward to the late eighteenth century, Great Britain was the Western production center for copper and copper alloys. Mines in Cornwall and smelting operations in Swansea, Wales were massive sources of copper (even before the time of the Romans).

Naval warfare resulted in much of the copper being commandeered for ship sheathing and the production of cannons. The British navy found that using copper alloy as sheathing for the undersides of its ships kept the Teredo shipworm from burrowing into the wooden hulls (and also deterred the growth of barnacles).

Thick bronze—Gunmetal—castings were built to equip the massive warships of European armies. These castings were elaborately decorated and became the largest single-use of copper for several centuries.

Copper’s Contemporary Appeal

In contemporary life, copper offers the design community a material for creating timeless beauty. When properly installed and maintained, copper and copper alloys will age gracefully in exterior applications—or they can be frozen with clear protective coatings of lacquers specifically created to protect the copper.

CUSTOM INTERIOR GLASS AND BRONZE SLIDING DOORS FOR THE WALKER TOWER LOBBY.

PHOTO © A. ZAHNER COMPANY.NORTH ENTRANCE FOR WALKER TOWER IN NEW YORK CITY.

PHOTO © A. ZAHNER COMPANY.INTERIOR SLIDING BRONZE DOORS.

PHOTO © A. ZAHNER COMPANY.The natural color that many copper alloys possess can be attractive and appealing, which is one of the reasons why coins have been (and still are) made from copper and copper alloys. The bright color of newly minted coins reflects the sense of value associated with the metal and its color.

Brightly polished brass is often found in the lobbies of buildings housing institutions of power and wealth. Elevator doors, entryways, handrails, and column covers made of copper alloys polished to produce a highly reflective golden appearance convey a sense of refinement few other materials can match.

Museum of the Bible BRONZE PANELS PRIOR TO PATINA APPLICATION.

PHOTO © A. ZAHNER COMPANY.The interiors of churches, synagogues, and mosques are adorned with ornamentation made from copper alloys that have been brightly polished to give a golden reflection, while many of their exteriors are clad in natural aging copper roofing.

Alloy C37700, a forging and machining alloy, was used on the artwork for the Museum of the Bible because it can handle extensive shaping and machining. A CNC Vertical Bridge Mill machine carved each line of text from the solid one-inch brass panels, often taking eight hours or more per piece to complete.

Blending Alloys for Elegant Contrast

The colors of the various alloys of copper have a natural elegance and can create tonal effects simply by placing one alloy next to another. If mirror polished or satin finished, the colors of the various alloys can show subtle yet intriguing differences in appearance and character.

CORINTHIAN HALL HISTORIC RESTORATION WITH REPLACEMENT GLASS AND PATINATED COPPER-ALLOY.

PHOTO © FARSHID ASSASSI.CORINTHIAN HALL CANOPY AT THE KANSAS CITY MUSEUM.

PHOTO © FARSHID ASSASSI.This variation of tones offers an esthetic palette for the artist and designer. When zinc is added to copper, the color becomes more golden yellow. Each percentage increase pushes the color of the wrought or cast form.

The addition of nickel takes the color to a golden silver, and the addition of aluminum takes the color to a yellow-gold tone.

A custom brass kiosk at The Midland Theatre in Kansas City shows such contrast. While the brass was left in its natural color and clear coated with Incralac lacquer, various alloys created subtle variations (C22000 wrought sheet for the fluted columns, C87300 for the columns’ capitals, C28000 for the top dome, and stamped C26000 for the entablature).

Copper Alloys For The Arts

Bronze has been a stalwart of artists and art collections for centuries. The most common form is cast bronze statuary. Techniques for casting bronze have been perfected by foundries over the years, with by far the most common being lost-wax casting. Usually, a patina is applied to the finished work.

Hands of Man by L. William Zahner

PHOTO © A. ZAHNER COMPANY.While bronze sculpture is still one of the most common uses of copper in art, the metal lends itself to many other forms. The sheet material can be hammered and shaped and is a favorite metal for chasing and repose work.

Copper’s ability to elongate without cracking and to be softened by annealing makes it well-suited for shaping. Working with sheet copper alloys, artists can create significant and beautiful surfaces by patinating the surface.

The Colorful Potential of Patinas

“Patinas . . . at their best they create a bit of magic or poetry that sings off the form.” —Rungwee Kingdon

Of all the metals, copper and copper alloys offer the most intriguing, natural, and beautiful color possibilities. The copper salts all possess remarkable and intense colors that we refer to as patinas. The methods by which these patinas develop and the chemical compounds they form are extensive.

15 RENWICK RESIDENTIAL DEVELOPMENT IN MANHATTAN WITH exterior copper panels.

PHOTO © A. ZAHNER COMPANY.The patination of copper is as old as the metal itself. Simply heating the surface of natural copper can produce a rainbow of interference colors, from gold to deep blues.

Our early ancestors experimented with creating patinas on copper and bronze surfaces. One of the most noted was the black patina known as niello, a black mixture of various substances mixed with sulfur to produce a paste.

Today, darkening methods involve oxidizing the surface to create statuary finishes (common chemical finishes used on copper and copper alloys).

DIRTY PENNY™ PREWEATHERED COPPER PATINA BY ZAHNER

PHOTO © A. ZAHNER COMPANY.STAR BLUE™ PREWEATHERED SURFACE PATINA ON COPPER BY ZAHNER.

PHOTO © A. ZAHNER COMPANY.Copper, Color, And The Alchemy Of Time

When a light wave strikes a copper surface, the portion of the wavelength from 600 to 700 nm is strongly absorbed. This absorption leads to reemission as reflected light. At the same time, copper absorbs the wavelengths at the blue and violet ends of the spectrum poorly. This gives copper a reddish color (and gold a yellowish color).

However, almost everyone is familiar with the beautiful patinas that are apparent on copper roofs built a century ago. These attractive, natural-looking green surfaces developed over time and with exposure to the atmosphere. They were not pre-colored but allowed to absorb the carbon, sulfur, and chlorine from the air.

The industrial age that introduced combustion products, first to heat our homes and factories and next to transport us about, sent an abundance of sulfur into the air. Copper captures the industrial pollutants of sulfur and carbon dioxide from the air and forms these beautiful green surfaces composed of copper sulfate, copper chlorides, and copper carbonates.

STATUE OF LIBERTY.

Photo by Brandon Mowinkel.Detail of copper canopy colonnade.

Photo © A. Zahner Company.The Statue of Liberty initially had the color of a penny when delivered. The copper began as a bright salmon-red color but was then exposed to the air, natural humidity, and rain. Dedicated in 1886, it was subject to years of exposure to the polluted environment of industrial New York, eventually forming the green patina we see today.

While yes, the patina is the result of surface corrosion, this tightly adhered compound protects the underlying metal. The rate of corrosion slows down significantly as this inert, mineral form of copper achieves a level of equilibrium with the surrounding environment.

The green patina we see on the copper roofs of decades-old buildings is composed of the mineral brochantite (a hydrated salt of copper composed of sulfur). The copper roof is intended to oxidize and grow a beautiful green tone that resists further oxidation.

A Modern Solution: Artificial Green Patinas

With the quality of air today, copper will take a significantly longer time to develop the characteristic green patina of old. Deep green natural patinas, which used to take a decade or so to develop, now will take close to a century or more.

Because of this designers have sought to accelerate the process by utilizing prepatinated material to capture the color tones from the beginning. The process does not use paints or dyes but the actual chemical process that nature would create over years of exposure.

COLUMBUS MUSEUM OF ART, EAST FACADE, GLASS, AND PATINATED COPPER.

PHOTO BY JEREMY PURSER, © A. ZAHNER CO.COLUMBUS MUSEUM OF ART, DETAIL OF THE CUSTOM COPPER SOFFIT.

PHOTO BY JEREMY PURSER, © A. ZAHNER CO.COLUMBUS MUSEUM OF ART PATINATED COPPER FACADE.

PHOTO BY JEREMY PURSER, © A. ZAHNER CO.Zahner engineers manufactured pre-weathered custom blue-green copper using a rapid patina process for the new Margaret M. Walter Wing of the Columbus Museum of Art. A process that normally takes twenty to thirty years was achieved in the span of a few weeks.

Is Copper Sustainable? Environmental Concerns and Opportunities

Sustainability involves striking a balance, an equilibrium in which the activities involved in producing and using a metal arrives at a workable and sustainable accord with the future.

This accord must consider the impact on the environment, the people working with the material, and the future generations affected. The continued enlightenment of the industry (to look beyond today and into the future) plays a relevant role in sustainability.

There is no question that mining practices in the last century have negatively impacted the environment. Thankfully, changes in thinking are occurring in many of the largest mining firms. Shortsightedness is being replaced with long term responsibility.

Today mining reclamation programs are in place to remove, filter, and neutralize mining water and to release clean water back into the environment. Meanwhile, copper is extracted from the water via an iron filtering system. This process of dewatering tailing ponds and flooded sites while recovering copper is in place at many of the largest mining operations throughout the world.

This is just one example of the many improvements occurring across the industry. Modern innovation in sustainable practices will propel copper’s impressive legacy as an intriguing and valuable metal into the next century.

Detail of the copper patina for the Daeyang Gallery and House.

Photo © A. Zahner Co.READ MORE: The Finishes, Patinas, and Textures of Copper

In our next installment of this series, we’ll explore the process of applying finishes, evoking a rainbow of patinas, and shaping texture into copper and copper alloys.

Read Part 2 in our series: The Finishes, Patinas, and Textures of Copper.

To find out more about using copper and how this material can be used in your next project, contact us for samples, or call +1 (816) 474-8882 to speak with one of our Project Specialists.

PHOTO © A. ZAHNER COMPANY.

PHOTO © A. ZAHNER COMPANY.

PHOTO © A. ZAHNER COMPANY.

PHOTO © A. ZAHNER COMPANY.

Photo ©

Photo ©

PHOTO ©️ Parrish Ruiz de Velasco (parrch.com)

PHOTO ©️ Parrish Ruiz de Velasco (parrch.com)

Ɱ, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license, edited.

Ɱ, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license, edited.