Zinc Guide Part 1: The Origins of Architecture’s Most Mysterious Metal

An Old World metal used for centuries across Europe, zinc is a relative newcomer to North American architecture, yet it has been embraced for the rich possibilities it has to offer the designer, architect, and artist.

Zinc was known by early alchemists as the metal that could turn copper into gold. When it was added to molten copper it would turn the copper to a beautiful golden color, but it was not gold.

The metal was also called counterfeht. It looked like silver, but it wasn’t. It was an imitation, a counterfeit. This odd metal, if it was a metal at all, was a mystery.

Zinc also went by the name spelter, used mainly by those who worked with the metal. Spelter was possibly a corruption of the name for “pewter,” the dull gray, lead-tin alloy. The Dutch were the first to import the metal into Europe and used the word spiauter referring to a mixture of lead and tin². It very well may have been an early marketing ploy to give value to this dubious metal.

Interior of a Laboratory with an Alchemist, David Teniers the Younger, 17th century, oil on canvas.

Photo © Science History Institute, Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license, unedited.Today, the modern name zinc has firmly taken hold, believed to have originated from the German word “zink,” which was derived from the Persian word “sing,” meaning stone as zinc ore deposits often have a rocky or stone-like appearance. On the periodic table of elements, its atomic number is 30 and is represented as Zn. It is a transition metal grouped with cadmium and mercury.

Zinc is silver with a slight bluish hue. It can be polished to a bright silver but quickly tarnishes when handled. As zinc ages it turns to a rich gray color with whitish oxides in areas where moisture is allowed to accumulate.

Most of the zinc found on the Earth’s surface is from hydrothermal activity bringing it near the surface. It is the 24th most abundant element within the upper crust of the Earth. Zinc is not found by itself, but rather in combination with other elements and metals.

A 1 cm3 cube of 99.995% pure zinc, a crystalline fragment of an ingot, and a sublimed dendrite.

Photo © Alchemist-hp, Free Art License, unedited.Early Refining and Creations in Zinc

As a metal, zinc in wrought or cast form came late, sometime in the middle of the sixteenth century, to Western civilizations. India and China were early zinc producers, using crucibles with charcoal to heat sphalerite, or zinc ore. They made coins from zinc in the fourteenth century. The Romans would produce brass from copper by adding zinc sulfide and heating it in small crucibles. The zinc was obtained by reducing the ore, releasing carbon dioxide, and the fumes of zinc would rapidly be absorbed into the copper. Once melted, the slag-covered block would be hammered, and a bright yellow color would appear.

A Roman army signal horn or "cornu", found in Alphen aan den Rijn, Netherlands.

PHOTO © Erfgoedhuis Zuid-Holland, Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International, Edited.Islamic Golden Age brass astrolabe.

PHOTO © Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1963, The Met Museum, Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication, Unedited.The reason zinc was one of the later metals to be discovered is due to the difficulty of refinement. Up until the mid-1700s, metals were made by roasting the ores and burning off the oxides to free the metal. Zinc has a low boiling point as metals go, which means that it would quickly turn to gas and the fumes would escape. Thus, the most common reduction for ore did not work for zinc as it simply escaped into the atmosphere.

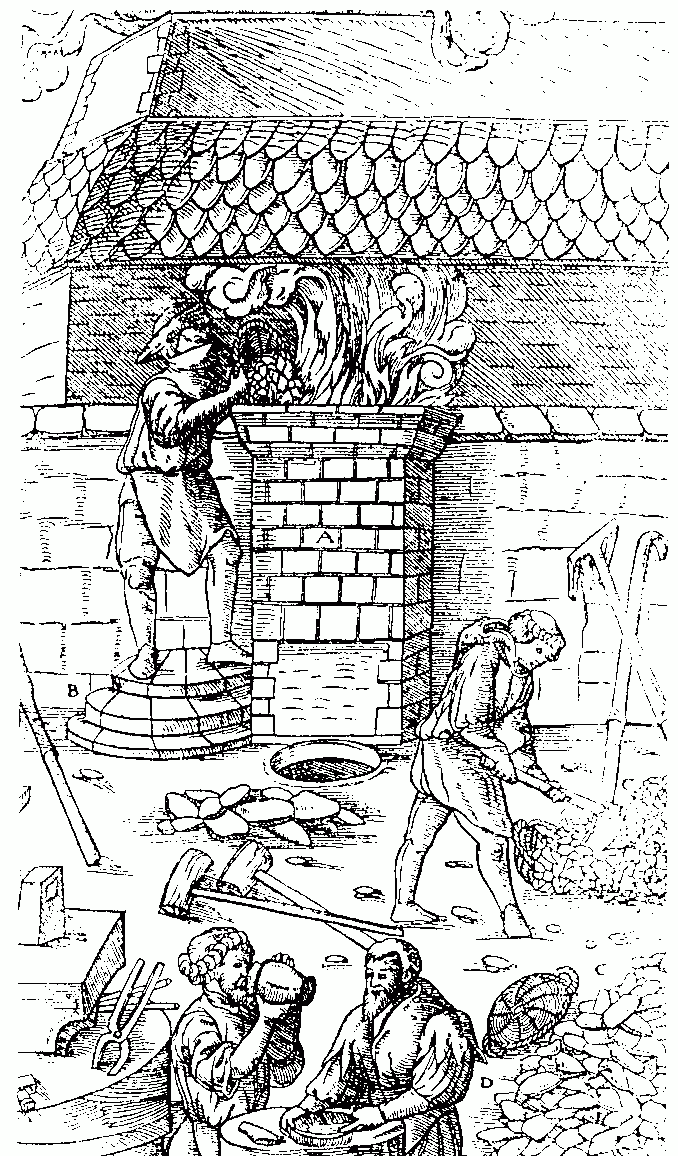

Early alchemists were first able to harvest zinc from a condensed film that would form on the walls of chimneys used to roast other metal ores that contained zinc such as lead, copper and silver. When the ores were heated the zinc would boil into vapor and condense on the stone, forming long, whiskery tuffs the alchemists called lana philosophica, meaning “philosopher’s wool.”

Assistants to the alchemists would collect this wooly substance by scraping it off the stone and out of the cracks of the chimney walls. The alchemists valued this special metal that was like tin, because when added to copper, it would transform the copper into a golden yellow.

Iron smelting in Middle-Age, from "De Re Metallica" by Georgius Agricola, 1556

Public domainRefining Zinc in Europe and the West

The discovery of zinc as a metal occurred in Germany around 1550 for the making of brass in the northern region around the Harz Mountains. The town of Goslar, Germany was a center of zinc mining and by 1650 large-scale zinc ore production and refinement was underway.

The mines around this region produced iron, silver, copper, lead, and zinc. The process of refining the metal was still a bit of a mystery to the west but by the middle part of the eighteenth century, zinc mining operations in Sweden and the region around Silesia, now present-day Poland, would become important sources for the ore.

Brass was the main product that created the demand for zinc. Brass, or Muntz metal as it was known in those days, was used to clad the hulls of English sailing ships. Named after its inventor, George Fredrick Muntz of Birmingham, England, it replaced copper as an anti-fouling cladding on the hulls of oceangoing ships as it was significantly cheaper than pure copper and would still protect the wood hulls from teredo shipworms. Muntz was also much stronger than copper.

Zinc Becomes Popular in Western Architecture

Zinc has had its high points and low points in art and architecture over the years. The skyline of Paris is a testimony to the beauty and durability of the metal with its silver-gray roofs and ornamentation that give the city its distinctive look.

Zinc mansard roof in Paris.

Baron Hausmann, Prefect of the Seine Department of France under Napoleon III, undertook a vast redevelopment of the city in the mid-1800s. This started the cladding of the famous mansards of Paris. The Baron supposedly had a relative in the zinc mining business, but his affinity for the metal could have also been due to his preference for lightly-colored stone used for the walls of his buildings that he didn’t want stained with the green runoff of oxidizing copper. One of the great benefits of zinc is that its oxides do not stain adjacent materials.

One of the main sources of zinc in France was the mine, La Vielle Montagne in Kelmis, called La Calamine in French. This area, on the border of Germany, was the source for much of the zinc used in Paris and the rest of France at the time. As early as 1815, some of the first roofs of Paris were clad in this silvery metal, and today close to 90% of the roofs of the city are still covered in zinc.

Galvanized steel surface with visible spangle.

Photo © TMg, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Germany, Unedited.Zinc and Galvanized Steel

It was soon discovered that coating iron in molten zinc would provide galvanic protection to the iron, and later steel. By 1830, coating iron with zinc was in wide use throughout Europe. Later in that century steel was invented and overtook iron as a building material. In fact, the vast majority of zinc used today is still used to protect steel by hot dipping it in baths of molten zinc.

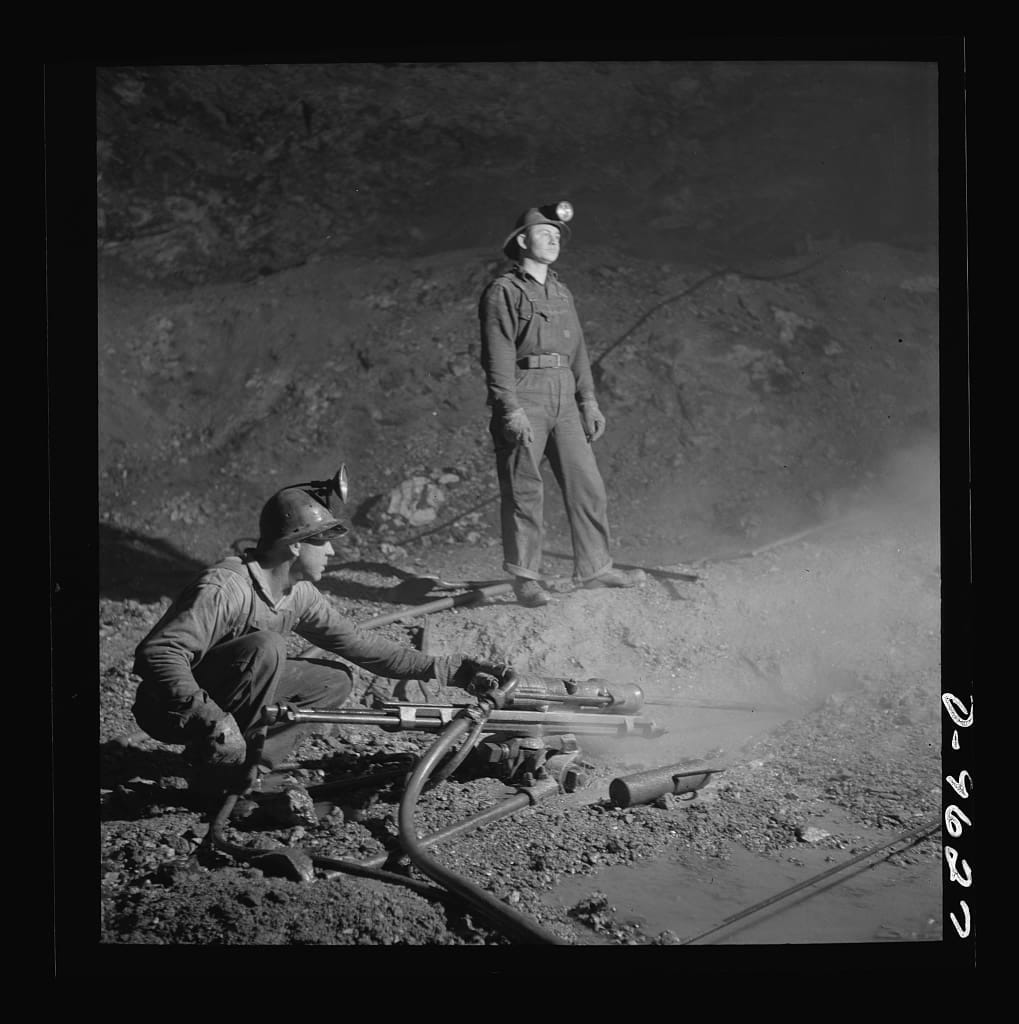

Blast hole drillers at a zinc mine of the Eagle-Picher Company near Cardin, Oklahoma.

Photo by Fritz Henle, Office of War Information, 1943. Public Domain.Once steel production was established, the need for zinc as its protective coating expanded and mining of zinc in the Americas began in earnest. Zinc mining and smelting expanded in various areas around the United States, with largest operations including Wisconsin, Illinois, and Missouri.

In the late 1800s and early 1900s American zinc mining accounted for the vast supply of ore for the world. The large European companies had exhausted much of their supply of high-quality ore and turned their attention to importing zinc from American mining interests.

Zinc As An Architectural Metal

Already popular in Europe, zinc was considered a metal of architecture and ornamentation in major cities including Paris, Berlin, and Brussels, giving those cities their distinctive looks.

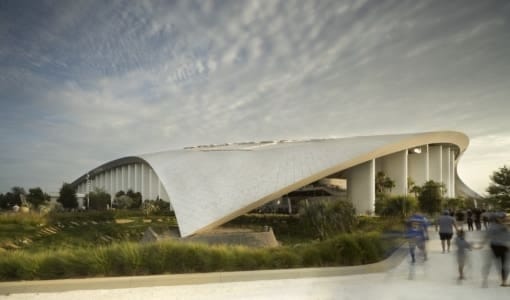

More recently zinc has been selected as a signature material for some of the most stunning architecture in the world. Daniel Libeskind chose zinc to clad the intricate shapes of the Jewish Museum in Berlin, as well as the Felix Nussbaum Haus in Osnabruck, Germany.

The zinc-clad Jewish Museum sits behind the Garden of Exile in Berlin, Germany.

Copyright: Photo © Avi1111 dr. avishai teicher, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license, unedited.The Winery Cantina de Il Bruciato in Carducci, Italy, is another excellent example of the modern use of zinc. The design firm Fiorenzo Valbonesi Cesena created an amazing addition to the Winery using preweathered zinc.

In the United States, however, the use of zinc began in the early twentieth century in the form of stamped panels and building ornamentation. But these panels were often painted which caused some confusion.

For example, the Folly Theater in Kansas City, Missouri, was constructed in 1900 then renovated in 1980. When the metal work was taken down to be repaired, the workers couldn’t identify it. The metal was different from the copper or terne-coated metal used on many of the buildings constructed in that era.

Zinc had disappeared in the United States as a building material, and those who had worked with sheet metal for decades had no idea what this metal was. Zinc had fallen out of the vocabulary of sheet metal workers for at least a generation in the United States. Replaced with lead-coated copper and terne-coated stainless steel, the blue-gray zinc was for the most part completely unknown.

The Folly Theatre, Kansas City, Missouri, circa 2010.

Copyright: Photo © Iknowthegoods, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license, unedited.The upper cornice, capitals, railings, and ornamentation around the windows of the Folly Theater were made from zinc and then painted. The balusters were spun zinc and soldered together. Other elements were stamped and joined with soldered seams. For the most part, the metal was in good condition, having performed quite well even though the building had suffered decades of neglect. The lack of knowledge of zinc as an architectural metal from those that worked with sheet metal architecture and the design community is a clear indication of why the metal was not used or considered for use.

It wasn’t until the late 1980s when large European zinc manufacturing companies set their sights on the vast North American market. More than 90% of the architectural use of zinc that exists today was built after this period. Zinc use has flourished and grown exponentially in the United States over the last three decades as education, knowledge and experience of this enigmatic blue-gray metal has expanded within the design community and the metal fabrication industry.

The Harvey M. Vaile Mansion, built in Independence, Missouri in 1881.

Photo © Photographs in the Carol M. Highsmith Archive, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.Zinc in Art

Zinc as an artistic material or architecturally aesthetic surface was slow to catch on in the United States. But in the late 1800s statues and monuments began to be manufactured from zinc. The movement began in Europe, mainly France, where it was called la statuomanie or statue mania. Statues proliferated throughout Europe and this eventually came to the United States as the Victorian era of architecture started.

Gothic and Italianate revival styles ushered in with the Victorian era made zinc popular, with elaborate zinc castings or stamped zinc sheeting used for both statue manufacturing and fenestration on Victorian homes.

Zinc was often treated to replicate the appearance of other materials such as bronze or stone. Plating copper on zinc was also common and considered a viable alternative to bronze sculpture.

A method of electroplating the zinc with copper came into widespread use as a way to obtain “bronze” for a more economical price. A true bronze sculpture might cost a hundred times that of a zinc sculpture. Sculptures made from zinc were quick and simpler to cast and the detail was similar.

Flatseam preweathered zinc panels on the Art Gallery of Alberta

Photo © Randall Stout ArchitectsZinc Sustainability and Safety

Today, zinc manufacturers in North America and Europe take the environment and environmental impact of their efforts seriously. Recycling of existing zinc currently stands at about 30% and is expected to increase as new systems of recovery bring the cost of recycling down.

Recycling zinc that has been used as a coating via the galvanizing process requires additional processes where the zinc is captured out of the vapor and dust from recycling steel. There are several processes that involve taking zinc out of the fumes generated from the melting and recycling of steel. As the steel is heated, the zinc melts and evaporates. From the vapors the zinc is removed and repurposed. Recycling zinc from sheet, scrap zinc, and stamped zinc is relatively straightforward.

Zinc: The Enigmatic Metal

Zinc is probably the least understood and most enigmatic of architectural metals, but more clarity is coming into the market every year.

We naturally want to classify zinc with labels and particular applications, but it really is different. Zinc is corrosion resistant, yet pairs well with other metals as an outer jacket. It is easy to form, until the temperature drops, then it gets brittle and can crack in cold forming. Where most metals harden as they cool, zinc relaxes. It can be molded and extruded, and sometimes acts more like a polymer than a metal.

No matter the application, its beauty, luster, and richness endure. And as new finishes, patinas and textures are developed, it will undoubtedly continue to gain favor with designers, architects and fabricators that want to make a lasting impression for centuries to come.

Custom raw zinc plate planters designed and fabricated by Zahner for the Spencer Art Museum.

PHOTO © A. ZAHNER COMPANY.Detail of zinc plate planter.

PHOTO © A. ZAHNER COMPANY.Enjoying this article? Take a deeper dive with:

Zinc Surfaces: A Guide to Alloys, Finishes, Fabrication, and Maintenance in Architecture and Art

By L. William Zahner

Zinc Surfaces, combines the latest guidance and information about zinc surfaces into a single and comprehensive resource for architects and artists everywhere. The visual, full-color book offers a highly visual, full-color guide to ensure architects and design professionals have the information they need to properly maintain and fabricate zinc surfaces. Numerous case studies illuminate and highlight the theoretical principles contained within.

Next: The Finishes, Patinas, and Textures of Zinc

In our next installment of this series, we’ll explore the various alloys, finishes and applications of zinc in art and architecture.

To find out more about using zinc and how this material can be used in your next project, contact us for samples, or call +1 (816) 474-8882 to speak with one of our Project Specialists.

PHOTO © A. ZAHNER COMPANY.

PHOTO © A. ZAHNER COMPANY.

Photo ©

Photo ©

PHOTO ©️ Parrish Ruiz de Velasco (parrch.com)

PHOTO ©️ Parrish Ruiz de Velasco (parrch.com)

Ɱ, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license, edited.

Ɱ, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license, edited.

Ɱ, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license, edited.

Ɱ, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license, edited.