The Metal Manufacturer behind Zaha Hadid’s latest American Project

How the Eli & Edythe Broad Museum’s builders left their comfort zones behind.

Earlier this week, City Pulse put out a story on the process of building the Eli & Edythe Broad Museum in Lansing, Michigan. Written by Lawrence Cosentino, the story features the process of how the museum was built, interviews with the key fabricators and builders, and the meeting of the project’s rapid schedule.

Excerpted below, Cosentino describes the introduction of Zahner into the project.

Meanwhile, hundreds of miles away, the museum’s most dramatic and visible feature was taking shape.

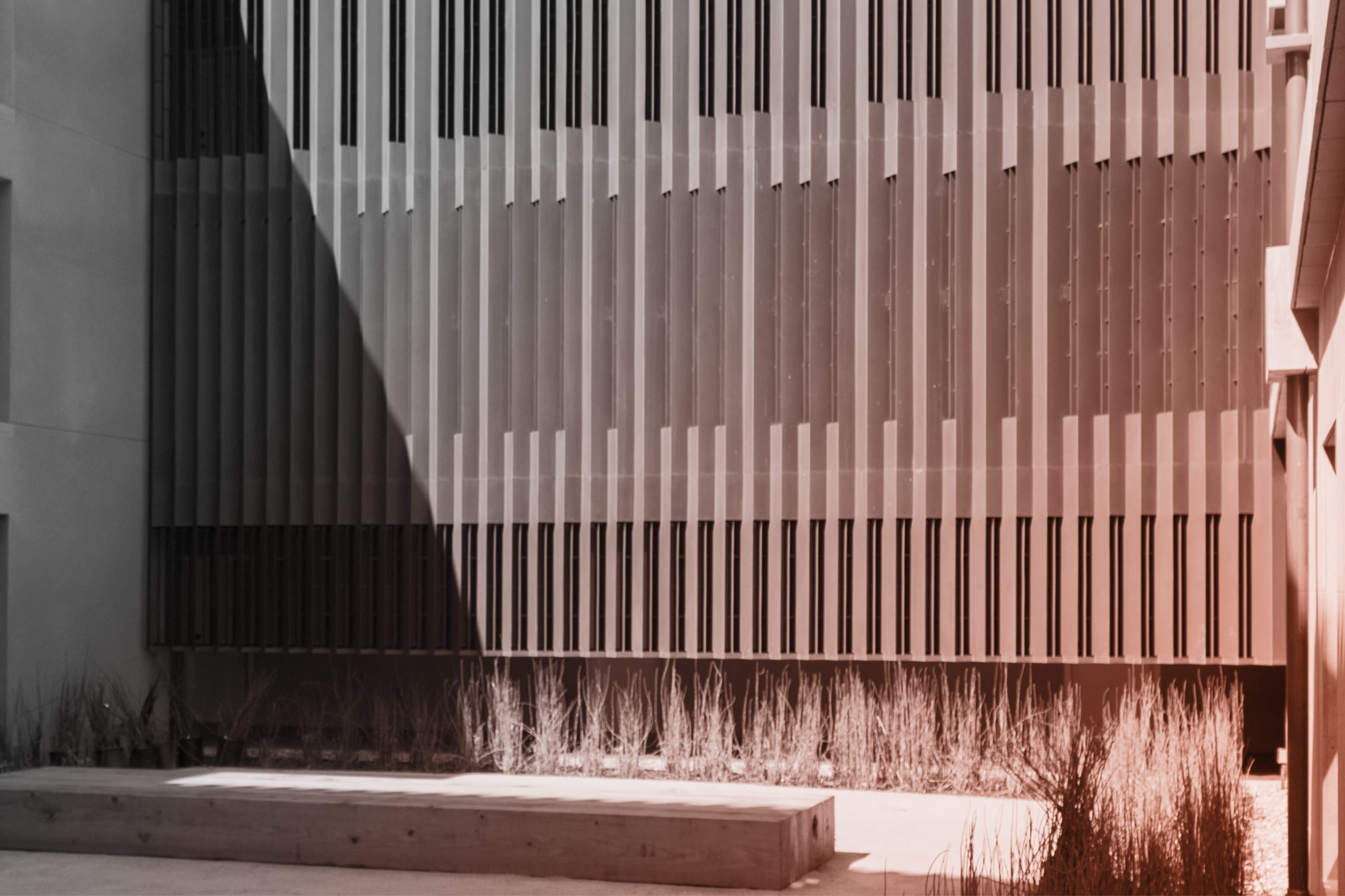

It fell to the A. Zahner Co. of Kansas City to craft the stainless steel pleats and fins that cover the building’s shell.

Zahner is renowned for doing impossible and breathtaking things with metal. To dress up the façade of a Neiman Marcus store in Massachusetts, CEO William Zahner and his team created a wavy stainless steel scarf 40 feet tall and 410 feet long. They wrapped Randall Stout’s Art Gallery of Alberta in a ribbon of stainless steel called the “borealis.” For architect Daniel Libeskind’s Jewish Museum of San Francisco, Zahner crafted a blue steel façade that changes color as the day goes on.

At the Broad Museum, Zahner wasn’t just churning out mega-cutlery from someone else’s pattern. The company was a “design assist” contractor, meaning that it was Zahner’s ulcer to manufacture and deliver Hadid’s vague pleat concept.

“I don’t even understand all the design that went into the pleats,” Bollman said.

To fold the pleats into crisp angles, a V-shaped cut needed to be made along the fold. It had never been done on the diagonal before. A first-of-its-kind mill, 20 feet long and 10 feet wide, was custom made in Wisconsin and shipped over to handle the angled folds.

“We were able to get a very sharp bend,” Zahner said. “This is the first diagonal V-cut job of any size anywhere on Earth.” Zahner kept the new mill and used it for delicate work on the 9/11 memorial unveiled last month in New York.The steel fins that slice through the museum on three sides presented special problems. Bringing huge pieces of sharp steel close to very expensive glass required lots of computer modeling.

“Those are monsters,” Zahner said. “We get really accurate, because the fins come within millimeters of the glass.”

Over the objection of Hadid’s designers, some of the fins were pulled out a few inches so workers could fit suction cups into the space and replace glass if it broke. The workings passed muster in a mockup on south campus and the fins were ready to go on the museum shell for real.

Zahner’s custom handiwork was dazzling, but most of it languished on loading docks as 2011 ticked by.

Delays were cascading over each other. Because the concrete, steel and glass schedules were out of whack, the steel pleats were “bounced all over the building rather than methodically going through from one end to the other,” as Bollman put it. “The project had seemed to grind to a halt.”

Zahner flew to the site from Kansas City, met with the construction team for almost five hours in summer 2011 and promised to beef up support. Bollman said that day was his happiest on the site.

Zahner said he would work with general contractor Barton Malow Co. of Southfield, Integrated Design Solutions of Troy and MSU “anytime.”

“Genuine people,” he said. “You call them up and talk to them about issues.”Meanwhile, Marshall worked out more of the building’s thorniest challenges. His proudest design element is a huge double door for big deliveries on the museum’s south wall that closes almost seamlessly, like the portal to the flying saucer in “The Day the Earth Stood Still.” The disappearing doors were needed because the museum is all front and no backside.

“It took a few months of my life getting those doors to close without scrunching the stainless steel,” Marshall said.

There was endless give and take between Hadid’s office and the troops on the ground, even when work shifted to interior finishes. Marshall set off a new round of negotiations when he balked at using stainless steel for the sleek heating grates inside the galleries.

“It wasn’t serviceable,” Marshall said. “We had to convince Zaha Hadid’s office to switch to aluminum.” Hadid demanded samples, a mock-up, and an explanation before accepting the solution.

The give-and-take extended to the landscaping around the museum. Marshall said MSU was fine with a building that “just sat there,” but Hadid’s team wanted the slopes and lines of the surrounding earthworks to extend and reflect the building’s design.

Plugging in to the environment is a crucial element of Hadid’s vision, from the giant wave of the London Aquatics Centre to the stream-and-boulders layout of the Guangzhou Opera House in China. Kiner fought hard to keep that vision for the Broad. “There’s almost a wave current of the building’s geometry that’s spread across the foot of the building, across the landscape,” Kiner said.

Meanwhile, hundreds of miles away, the museum’s most dramatic and visible feature was taking shape.

It fell to the A. Zahner Co. of Kansas City to craft the stainless steelpleats and fins that cover the building’s shell.

Zahner is renowned for doing impossible and breathtaking things with metal. To dress up the façade of a Neiman Marcus store in Massachusetts, CEO William Zahner and his team created a wavy stainless steel scarf 40 feet tall and 410 feet long. They wrapped Randall Stout’s Art Gallery of Alberta in a ribbon of stainless steel called the “borealis.” For architect Daniel Libeskind’s Jewish Museum of San Francisco, Zahner crafted a blue steel façade that changes color as the day goes on.

At the Broad Museum, Zahner wasn’t just churning out mega-cutlery from someone else’s pattern. The company was a “design assist” contractor, meaning that it was Zahner’s ulcer to manufacture and deliver Hadid’s vague pleat concept.

“I don’t even understand all the design that went into the pleats,” Bollman said.

To fold the pleats into crisp angles, a V-shaped cut needed to be made along the fold. It had never been done on the diagonal before. A first-of-its-kind mill, 20 feet long and 10 feet wide, was custom made in Wisconsin and shipped over to handle the angled folds.

“We were able to get a very sharp bend,” Zahner said. “This is the first diagonal V-cut job of any size anywhere on Earth.” Zahner kept the new mill and used it for delicate work on the 9/11 memorial unveiled last month in New York.

The steel fins that slice through the museum on three sides presented special problems. Bringing huge pieces of sharp steel close to very expensive glass required lots of computer modeling.

“Those are monsters,” Zahner said. “We get really accurate, because the fins come within millimeters of the glass.”

Over the objection of Hadid’s designers, some of the fins were pulled out a few inches so workers could fit suction cups into the space and replace glass if it broke. The workings passed muster in a mockup on south campus and the fins were ready to go on the museum shell for real.

Zahner’s custom handiwork was dazzling, but most of it languished on loading docks as 2011 ticked by.

Delays were cascading over each other. Because the concrete, steel and glass schedules were out of whack, the steel pleats were “bounced all over the building rather than methodically going through from one end to the other,” as Bollman put it. “The project had seemed to grind to a halt.”

Zahner flew to the site from Kansas City, met with the construction team for almost five hours in summer 2011 and promised to beef up support. Bollman said that day was his happiest on the site.

Zahner said he would work with general contractor Barton Malow Co. of Southfield, Integrated Design Solutions of Troy and MSU “anytime.”

“Genuine people,” he said. “You call them up and talk to them about issues.”

Meanwhile, Marshall worked out more of the building’s thorniest challenges. His proudest design element is a huge double door for big deliveries on the museum’s south wall that closes almost seamlessly, like the portal to the flying saucer in “The Day the Earth Stood Still.” The disappearing doors were needed because the museum is all front and no backside.

“It took a few months of my life getting those doors to close without scrunching the stainless steel,” Marshall said.

There was endless give and take between Hadid’s office and the troops on the ground, even when work shifted to interior finishes. Marshall set off a new round of negotiations when he balked at using stainless steel for the sleek heating grates inside the galleries.

“It wasn’t serviceable,” Marshall said. “We had to convince Zaha Hadid’s office to switch to aluminum.” Hadid demanded samples, a mock-up, and an explanation before accepting the solution.

The give-and-take extended to the landscaping around the museum. Marshall said MSU was fine with a building that “just sat there,” but Hadid’s team wanted the slopes and lines of the surrounding earthworks to extend and reflect the building’s design.

Plugging in to the environment is a crucial element of Hadid’s vision, from the giant wave of the London Aquatics Centre to the stream-and-boulders layout of the Guangzhou Opera House in China. Kiner fought hard to keep that vision for the Broad. “There’s almost a wave current of the building’s geometry that’s spread across the foot of the building, across the landscape,” Kiner said.

The Broad Museum will be more expensive to maintain than an ordinary campus building. Bollman didn’t have an estimate. “We don’t have a stainless steel building on campus, so we don’t know what it will take to wash it.” (Zahner said it only needs a power wash twice a year, like a garage.)

Wherever possible, Marshall specified local, or at least American-made, hardware. The huge west gallery’s ceiling lights, which seem to stretch into infinity, are smartly hooded four-foot fluorescent tubes the university buys by the truckload.

All parties agreed that the Broad Museum has very little that’s off the rack. It comes with the territory when you build a design by Zaha Hadid.

“I don’t think we’ll ever see anything like this on this campus,” Bollman said. “It’s truly a once in a lifetime experience.”

Until the press starts to pour in, the Broad Museum’s builders can bask in the approval of the client and the architect.

“It’s exactly what we had hoped,” said Linda Stanford, MSU project manager and architectural expert. “It’s a building that challenges you in that space, because you are an active participant.”

The Broad Museum will be more expensive to maintain than an ordinary campus building. Bollman didn’t have an estimate. “We don’t have a stainless steel building on campus, so we don’t know what it will take to wash it.” (Zahner said it only needs a power wash twice a year, like a garage.)

Wherever possible, Marshall specified local, or at least American-made, hardware. The huge west gallery’s ceiling lights, which seem to stretch into infinity, are smartly hooded four-foot fluorescent tubes the university buys by the truckload.

All parties agreed that the Broad Museum has very little that’s off the rack. It comes with the territory when you build a design by Zaha Hadid.

“I don’t think we’ll ever see anything like this on this campus,” Bollman said. “It’s truly a once in a lifetime experience.”

Until the press starts to pour in, the Broad Museum’s builders can bask in the approval of the client and the architect.

“It’s exactly what we had hoped,” said Linda Stanford, MSU project manager and architectural expert. “It’s a building that challenges you in that space, because you are an active participant.”

Read the full, unexcerpted vers

ion of the article at the Lansing Pulse, November 7,2012.

PHOTO © A. ZAHNER COMPANY.

PHOTO © A. ZAHNER COMPANY.

PHOTO © A. ZAHNER COMPANY.

PHOTO © A. ZAHNER COMPANY.

Photo ©

Photo ©

PHOTO ©️ Parrish Ruiz de Velasco (parrch.com)

PHOTO ©️ Parrish Ruiz de Velasco (parrch.com)

Ɱ, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license, edited.

Ɱ, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license, edited.