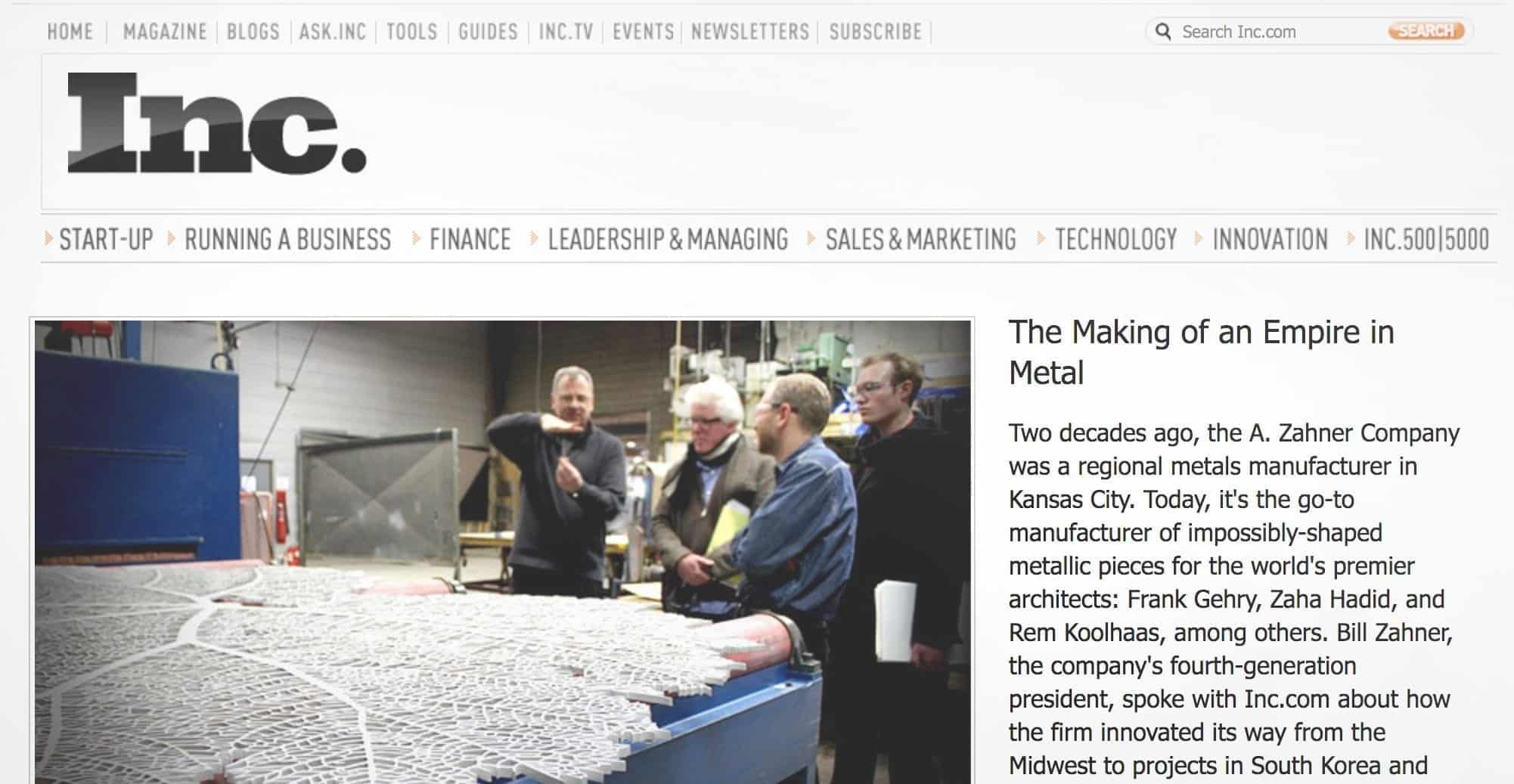

The Making of an Empire in Metal

From Metal Factory to Architectural Innovator, by Reeves Wiedeman on Inc.com

This article appeared originally in Inc Magazine, and is excerpted with permission from the publisher:

Two decades ago, the A. Zahner Company was a regional metals manufacturer in Kansas City. Today, it is the go-to manufacturer of impossibly-shaped metallic pieces for the world’s premier architects: Frank Gehry, Zaha Hadid, and Rem Koolhaas, among others. Bill Zahner, the company’s fourth-generation president, spoke with Inc. Magazine about how the firm innovated its way from the Midwest to projects in South Korea and Qatar.

“As a kid I was intrigued by these big projects that were done by famous architects. There wasn’t much architectural work in Kansas City, so I pushed the company to look elsewhere.”

When Bill Zahner joined the family business in 1978, conventional wisdom said the company should stay local, as it had for nearly a century. But he decided the future was in high-end architectural work—the company did mostly roofing and siding— and to do that, it had to look beyond its home. “As a kid I was intrigued by these big projects that were done by famous architects,” Zahner said. “There wasn’t much architectural work in Kansas City, so I pushed the company to look elsewhere.”

Traveling to conferences around the country, Zahner met a number of architects, including Frank Gehry, who began consulting with Zahner on how to use different metals. In 1993, the pair collaborated on the Weisman Art Museum in Minneapolis, with Zahner designing the giant metallic pieces that made the museum look like a series of billowing sails rising above the Mississippi River. “I remember it came out on the front page of USA Today,” Zahner says. “It was the first real project for us that got a lot of attention, and it put Frank in a whole new level. It helped establish that ribbon-y look he had.”

Welcoming the 21st Century

When Zahner joined the company, it had no computers (“Even accounting didn’t have them,” he says). The Experience Music Project, another Gehry building, helped change that. Zahner was forced to invest heavily in technology and rethink its entire production scheme to meet the difficulties of the new project: 4,000 curving metal panels, each completely unique, that were not only decorative but also structurally essential. “You want to start with something small,” Zahner said. “But with Frank, you don’t start producing a little handkerchief. You start with something to cover your whole city.”

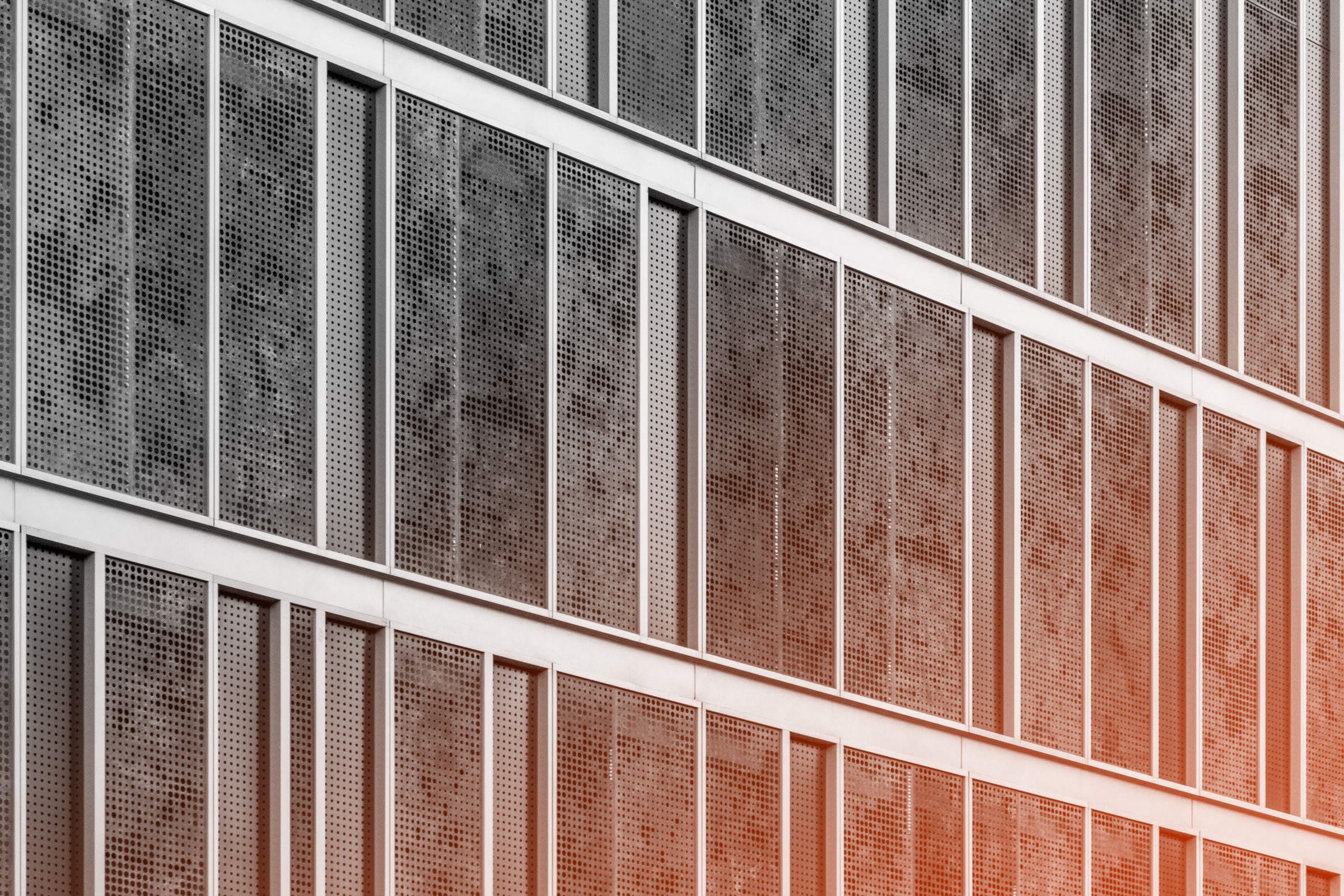

In its early years, Zahner’s research and development was driven by the demands of its commissioned jobs. Now, employees work on whatever interests them. Direct R&D comes to about four percent of volume, but, “indirectly, we’re constantly coming up with new things,” Zahner said. Among the current pet projects: improving a patented process that superimposes photographs or other images onto metal. The process was used on the de Young Museum, in San Francisco, where a photo of trees near the museum covered the building’s copper walls.

“Norman Foster wanted a surface like no one has ever seen,” said Zahner, referring to his work on the British architect’s spaceport in New Mexico. At the time, Zahner and several of his engineers had been experimenting with heat, exposing different copper alloys to temperatures around 10,000 degrees. “Portions of the alloy constituents come out, and you get these really wild looking surfaces,” said Zahner, before pausing. “I don’t know if he likes them yet.”

Sharing an Innovative Spirit

In the early 90s, Zahner began research into how various metals could be best applied in different situations. That became a 400-page book, “Architectural Metals,” to which Gehry contributed a foreword. More than 5,000 design firms around the country bought the manual, which established the company as innovators in the world of metal. “The book established trust between us and our clients,” Zahner says. Today, the company connects with architecture lovers through an iPhone app.

Zahner is an amateur sculptor—”I wish I had more time for it”—and prefers to hire engineers with a similarly creative bent. “The nature of what we do is to make the connection between art and science,” Zahner said. “We like to work with really good minds that can be more creative, and they need to have an interest in art.” Today, ten percent of Zahner’s work is with sculptors and other artists, and several of his employees are art institute graduates. The company will also help employees pursue a variety of advanced degrees.

Zahner said that Gehry’s planned Eisenhower Memorial, in Washington, D.C., is “one of the most difficult things I’ve ever worked on.” The design involves several steel “tapestries,” which require a complicated process called weaving. Gehry looked to China and Japan for technology that could do the job, but settled on Zahner, which has been working with artists at the Kansas City Art Institute to hash out a solution. “It’s doing something with metals that has never been done before,” said Zahner. “If it works, it’ll be unbelievably gorgeous.”

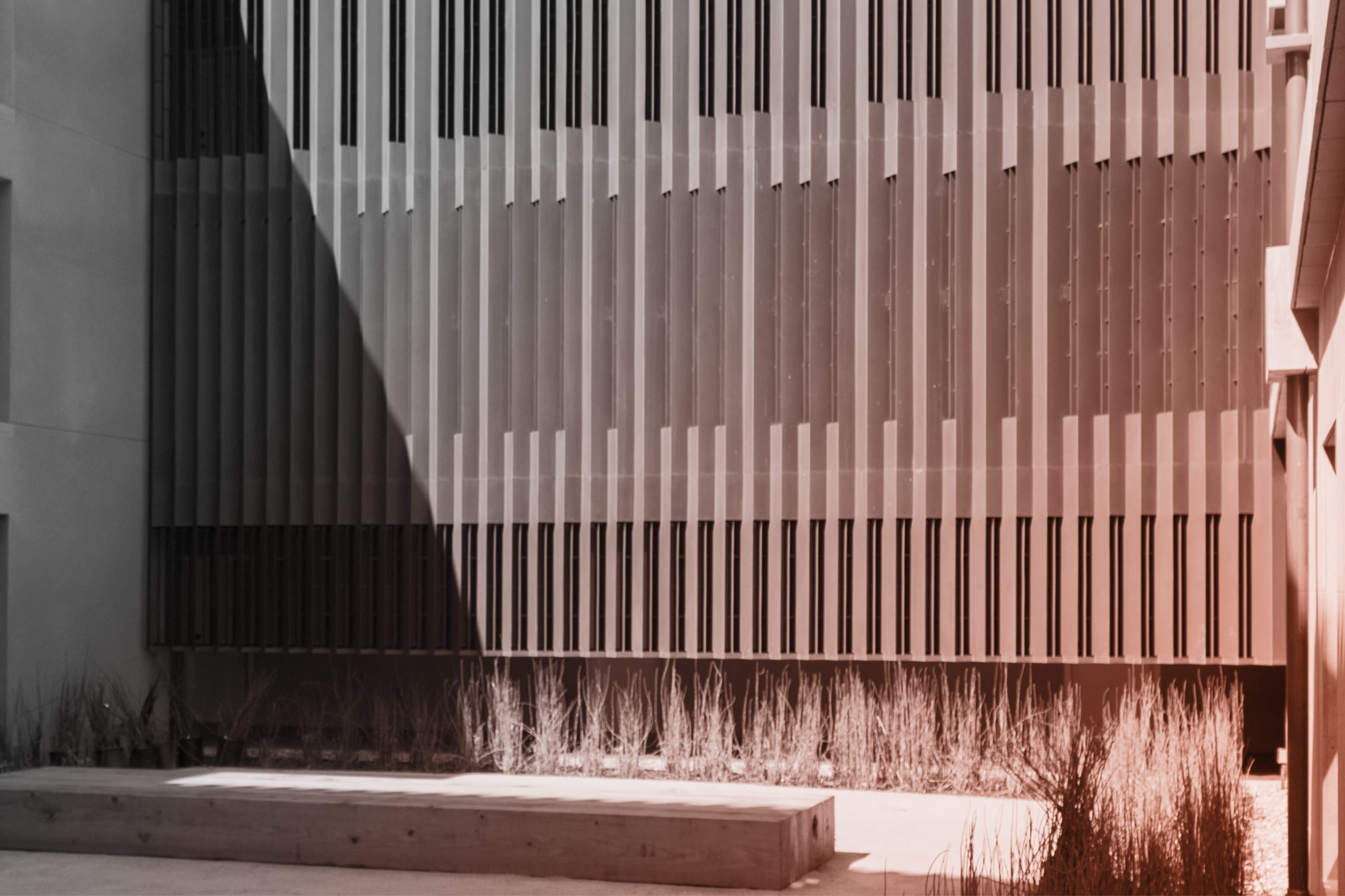

The company’s most sensitive project to date is the September 11th Museum at Ground Zero, scheduled to open on the 10th anniversary of the attacks. Zahner is designing the building’s “envelope”— its outer walls and roof—with alternating metallic surfaces that give it a striped appearance. “It’s been a tricky project, to say the least,” says Zahner. “The work has to be of incredibly high quality.”

Read the photo story, From Metal Factory to Architectural Innovator, by Reeves Wiedeman on Inc.com

PHOTO © Tim Hursley

PHOTO © Tim Hursley

PHOTO ©️ Parrish Ruiz de Velasco (parrch.com)

PHOTO ©️ Parrish Ruiz de Velasco (parrch.com)

© Fedora Hat Photography

© Fedora Hat Photography Photo by Andre Sigur | ARKO

Photo by Andre Sigur | ARKO

Ɱ, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license, edited.

Ɱ, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license, edited.