Get Inspiration, Delivered.

Join our newsletter and get inspiring projects, educational resources, and other cool metal stuff, straight to your inbox.

Stainless steel may be relatively new as a building material, but it is the undisputed king of architectural metals. In the hands of a knowledgeable fabricator, stainless steel offers infinite variations of finishes and textures that can be mixed, layered, etched, and embossed to create a surface appearance and reflectivity like no other.

Add to this the strength, hardness, and corrosion resistance stainless steel offers, and you have a very special material of design.

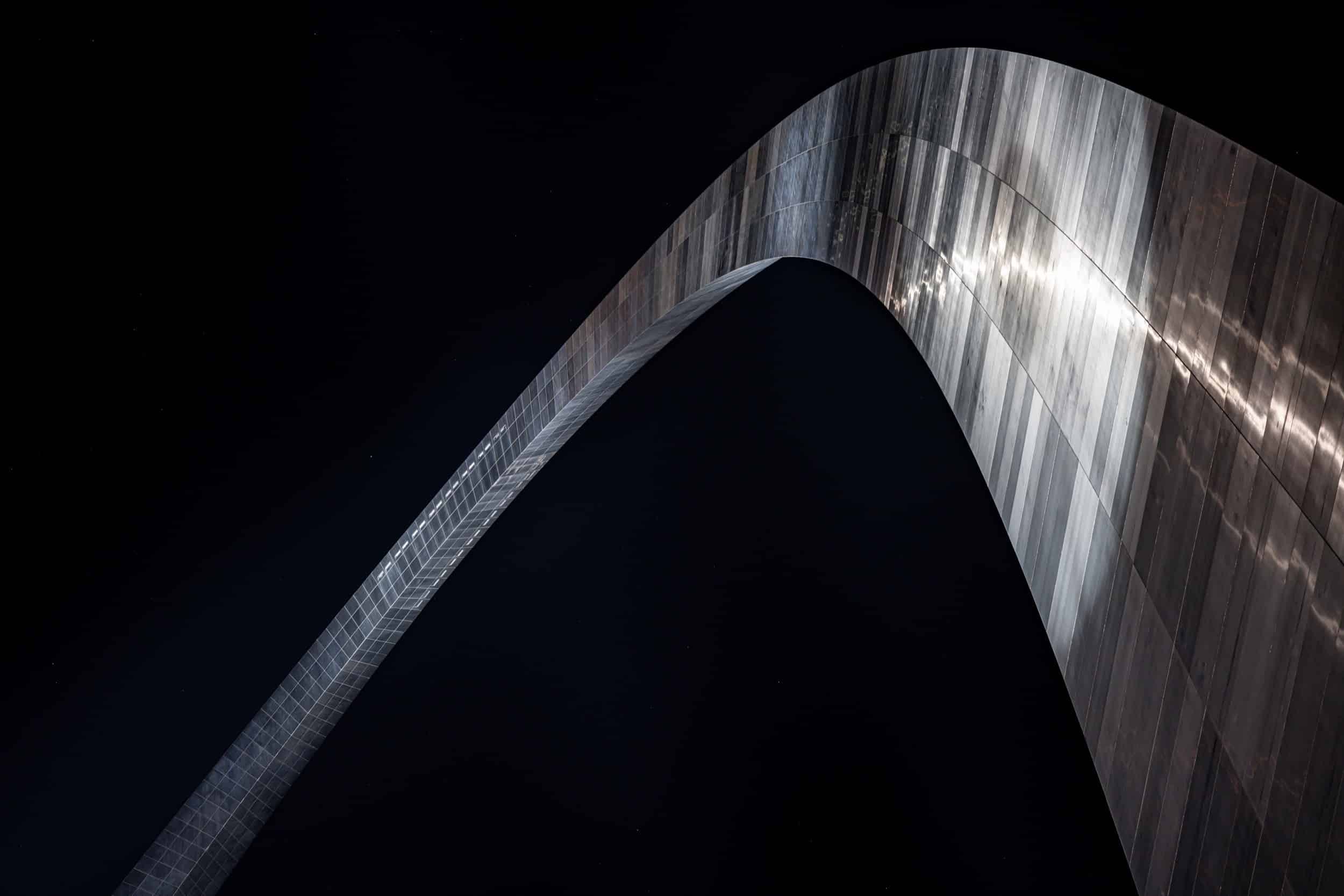

Ever since Eero Saarinen selected it as the outer shell of the Gateway Arch in St. Louis in the early 1960’s, stainless steel has become a favorite choice of designers and artists worldwide because of its superior qualities and enduring appeal.

Eero Saarinen’s GateWay Arch in St. Louis, Missouri.

A Modern Metal With Jewel-Like Luster

Stainless steel does not have the long history of copper, bronze, or zinc. Even aluminum was in use before stainless steel came into prominence. Its discovery and subsequent utility was not known prior to the twentieth century, and in fact got its humble start in cutlery.

Today, stainless steel is synonymous with the modern age. Art conservationists consider it one of the so-called modern metals. Stainless steel’s jewel-like luster adorns building facades and roofs on many major structures around the world.

Perhaps the most compelling reason to consider using stainless steel is the brightness of the metal. The shine of stainless steel is rich and intense. Unlike the warmth attributed to silver and pewter, stainless steel conveys a sense of modern achievement as a material that can stand the test of time.

The color is attributed to the chromium in the alloy, which gives stainless steel a bluish tone. Some would consider this tone cold and sterile, but when stainless steel is given a finishing texture of miniscule scratches or tiny indented glass bead–blasted craters… the metal captures the light and sends it back to us in ways that no other material can.

Detail of the Angel Hair stainless steel surface on the Fisher Center at Bard College.

Photo © A. Zahner Company.

“Vibration” finish offered by industry manufacturers.

PHOTO © A. ZAHNER COMPANY.

History of Stainless Steel in Art and Architecture

Stainless steel came into use as an architectural surfacing material in the late 1920s, the first major work being the Chrysler Building in New York. The Chrysler Building is clad in stainless steel with an alloy content resembling alloy S30200.

The Chrysler building was complete in May 1930.

PUBLIC DOMAIN.

stainless steel hood ornament on the Chrysler building.

PUBLIC DOMAIN.

The Chrysler building’s distinctive Art Deco crown and spire.

PUBLIC DOMAIN.

The person who actually “invented” stainless steel is up for debate. Some credit Harry Brearley of England, who in 1913 created a steel composed of 12.8% chromium.

This chromium steel was used early on for cutlery, because it could hold a sharp edge without corroding. Brearley called it “rustless steel.” In a trade journal, it was later described as stainless steel by Ernest Stuart of the R.E. Mosley cutlery company. The name stuck and was used to describe this new steel that would not corrode.

In the United States around this same time, there were several people involved with the development of steel alloys high in chromium. Elwood Haynes started the Haynes Stellite Works in 1914 and produced a chromium-tungsten steel alloy. In 1907 he filed for and was awarded a US patent, No. 873,745, on chromium and cobalt alloy steels.

In 1919, Haynes was awarded a patent for a specific range of chromium steels when he submitted several samples of his stainless steel to the patent office. He eventually sold his US patents to Harry Brearley, who started the American Stainless Steel Company.

A Turning Point In The Industrial Revolution

This new metal—that had the strength of steel but was corrosion resistant, possessed a luster that rivaled silver yet would not tarnish, and that was heat resistant, hard yet malleable, and affordable—entered the realm of industry.

Stainless steel moved mankind to another evolutionary stage of the industrial revolution. These advances in metallurgy mark a period of time in the mastery of metals by mankind that has never before or since been equaled.

The uses for stainless steel exploded after the early 1920s, as the number of manufacturers and the advancement of metallurgical knowledge extended the beneficial characteristics of these chromium-bearing steels.

In these early years, the United States alone had nearly 100 companies making different forms of stainless steel. Each had its own trade name associated with the various forms of the metal produced.

Today, the name stainless steel is ubiquitous across most of the world as a term for chromium bearing steels. In some regions of Europe, stainless steel is known instead as “Inox” (after the French term “inoxydable”) or as “Rostfrei” (German for “rust free”).

A Remarkable Metal Of Our Modern Age

The choice of stainless steel as a design component brings to bear the confluence of nature and technology. Stainless acts as a natural material. From the earth and the sky in the form of meteorites, you have iron and nickel, two common metals that add strength and resilience.

Stainless steel is the name given to a group of steel alloys that contain various levels of chromium. At least 10.5% chromium is needed for a steel alloy to be included in the family of stainless steels. Other elements, such as nickel and molybdenum, are added in various amounts to give this special steel alloy attributes of value for art and architecture.

This chromium-alloyed steel, given the name “stainless,” possesses the property of a very stable, unchanging surface. Unfortunately, to the uninitiated the name is sometimes misleading. Stainless steel gets its “stainless” character from the thin chromium oxide film that forms over the entire surface when it is exposed to the atmosphere. The face side, reverse side, and edges all develop this thin, unbroken chromium oxide protective layer.

OHR-O’KEEFE MUSEUM ROOF SYSTEM FEATURING ANGEL HAIR STAINLESS STEEL.

PHOTO © A. ZAHNER COMPANY.

If, however, this film is damaged or breached by exposure to certain corrosive environments, stainless steel will perform no better than a high grade of steel.

When exposure to deicing salts and humid coastal conditions change the surface appearance of stainless steel by its forming first a thin dark stain and then spots of dark red, the first thought is that the metal is not stainless steel but some inferior substitute.

Once the stains are cleaned and the salts removed, the stainless steel will return to its original luster. There is no chicanery in the naming of this metal.

It truly is a remarkable metal of our modern age. One only needs to perform an occasional cleaning and prevent mainly chloride ions from remaining on the surface for a long period of time.

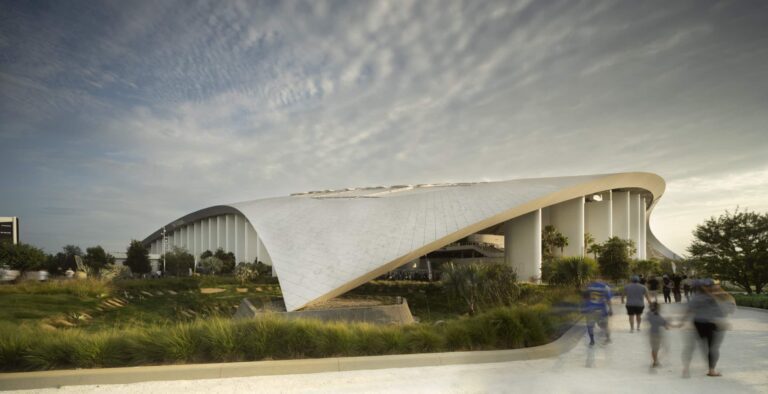

HARIM GROUP HEADQUARTERS ENTRANCE HAS A CURVING STAINLESS STEEL FACADE SYSTEM MADE BY ZAHNER.

PHOTO © MIJIE.

Durable, Reflective, Adaptable

One of the few metals expected to stand against nature and not change in perceivable ways, stainless steel is homogeneous in its makeup. Scratch it, cut it, or pierce it, and you have the same stainless steel throughout. It does not require other metals to protect it, nor does it need paint to seal its surface from the rigors of the environment.

Stainless steel is a noble metal in its passive state (nonreacting and stable). This serves as an advantage in art and architecture. Because of this passive state, bolts and fasteners made from stainless steel support many steel and aluminum structures. Even copper roofs can be held down with stainless steel clips without fear of galvanic reaction.

Like titanium, another metal even more recently introduced to the cladding scene, thin skins of stainless steel can enclose structures and be expected to last hundreds of years with little maintenance.

AMBIENT REFLECTIVITY OF THE ANGEL HAIR STAINLESS STEEL PANELS BY ZAHNER FOR THE OHR-O’KEEFE MUSEUM OF ART.

PHOTO © A. ZAHNER COMPANY.

Stainless steel reflects around 60% of the visible light spectrum. It absorbs the shorter wavelengths of the visible spectrum, which is the blue end. One would think that if it absorbs more of the blue spectrum, then the color reflected would be reddish, but that is not so. Stainless steel has a markedly bluish tint.

In terms of corrosion resistance, there are few other metals that show such a disregard for the ravages of the environment. Stainless steel is slow to change – unless confronted by chlorides (which have a proclivity for metals and stainless steel is no exception). There are alloys, however, that have been developed to fend off the attack.

This corrosion resistance characteristic of stainless steel is the attribute that enables the metal to be a changeless design material in the typical environment of our cities and towns.

Finishes And Textures

Stainless steel used as a cladding material inside or outside can be enhanced further by the choice of the finishing texture. These finishes essentially paint with light.

A skillful choice of finish can enhance what the eye will see as the full potential of the luster of stainless steel is brought out. Designers and artists have a multitude of choices and combinations when working with stainless steel to emphasize their creations.

Surface treatments, both mechanical and chemical, take advantage of the reflectivity afforded by the chromium in the alloy and by the consistency and predictability of the surface.

This is the main attribute that makes stainless steel so desirable. Innumerable finishes and textures can be introduced to the surface of stainless steel in order to take advantage of this beautiful, consistent luster.

GOLD LIGHT INTERFERENCE STAINLESS STEEL WITH DEEP UNDULATED SURFACE.

PHOTO © A. ZAHNER COMPANY.

BLUE LIGHT INTERFERENCE STAINLESS STEEL ON THE TEAM DISNEY IN ANAHEIM.

PHOTO © A. ZAHNER COMPANY.

Stainless steel can be given color from controlled development of interference oxides or from physical vapor deposition (PVD) coatings that also produce a thin interference oxide on the surface. The colors are limited by the reflective index of the film or oxide, but they can be enhanced further by first applying various mechanical surface finishes to the base metal surface.

This capability makes stainless steel one of the more versatile metals for art and architecture design. The metal surface’s ability to resist change when exposed to ambient conditions allows for a predictable appearance that is sustainable for a long period of time. No further barrier coatings are necessary, and the mineral nature of the surface does not change as a result of exposure to ultraviolet radiation from sunlight.

Profile of the completed wave facade on top of the Sea Turtle Cafe at Omaha’s Henry Doorly Zoo.

Photo by Alexandra Hoffman, ARKO | © A. Zahner Company

Next: The Finishes, Colors, and Light Waves of Stainless Steel

In our next installment of this series on stainless steel, we’ll explain the process of applying finishes and patterns, including glass bead-blasting, etching, buffing, sanding, and interference coloring.

Read Part 2 in our series on stainless steel: The Finishes, Colors, and Light Waves of Stainless Steel.

To find out more about using stainless steel and how this material can be used in your next project, contact us for samples, or call +1 (816) 474-8882 to speak with one of our Project Specialists.