Get Inspiration, Delivered.

Join our newsletter and get inspiring projects, educational resources, and other cool metal stuff, straight to your inbox.

This month, in an article by Kriston Capps for The Atlantic, Kansas City’s A. Zahner Company gets a nod for being a powerhouse of unique architecture built in America.

“Even if they wind up somewhere else, the most interesting American buildings are constructed in Kansas City.”

– Kriston Capps, The Atlantic.

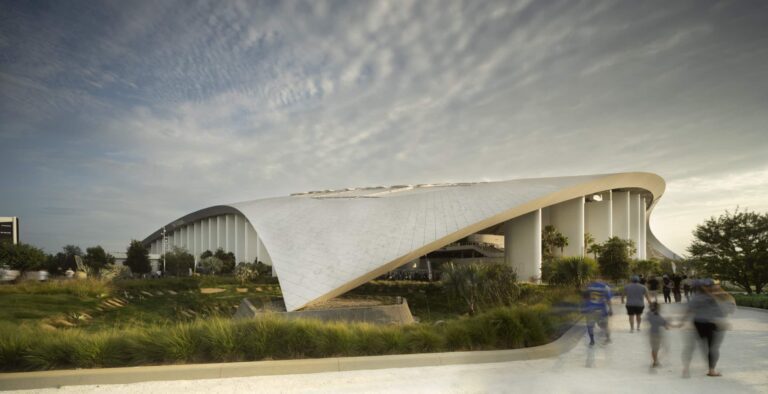

Kriston Capps visited Zahner’s Kansas City facility during the production of Petersen Automotive Museum. Located in Los Angeles, the museum’s complex facade was manufactured by Zahner in Kansas City. Zahner installers in Los Angeles were able to complete the project ahead of schedule. The museum will re-open at the end of 2015.

Designed by Kohn Pedersen Fox, Zahner was responsible to Matt Construction and the architects at KPF. Zahner fabricated and installed the surface, form, and structural components for the Petersen Museum’s complex facade.

PHOTO © A. ZAHNER COMPANY.

Becoming Kansas City’s Powerhouse for Architecture

Zahner wasn’t always known for creating complex architecture. In the late 20th century, the company began a transformation. The article provides a brief history of how Zahner went from being Kansas City’s regional manufacturer of “tin roofs” to a creative resource for top designers around the world:

For most of its 118 years, the firm was a sheeting and decking company with a steady business in tin roofs. That changed in 1983, when L. William Zahner—the great-grandson of the company’s founder—met the architect Frank Gehry. At the time, Gehry was just beginning to explore erecting curvilinear designs with seemingly impossible materials. Zahner then worked with Gehry to fabricate the frenetic steel-and-aluminum exterior of the Experience Music Project, in Seattle, a pathbreaking achievement for metals and architecture alike.

The author, Kriston Capps, spent an afternoon at the Zahner Headquarters in Kansas City, where he saw how the sheet metal workers made the Petersen Museum’s curved architectural panels.

Constructed using 308 mega-panels, these structural aluminum assemblies bolt together to create seamless ribbons which wrap the building. These massive panels were all manufactured in Zahner’s KC shop. There, the fabricators, clad each panel in 14-gauge A304-stainless steel on the exterior face and red-painted aluminum on the interior face.

Each of these mega panels are pre-assembled in Kansas City, shipped to the site, and installed one-by-one to create an exterior shell. This web of stainless steel ribbons covers the entire outer surface of the museum’s renovated building.

PHOTO © A. ZAHNER COMPANY.

PHOTO © A. ZAHNER COMPANY.

Capps’ article also describes some of the restoration and historical projects that Zahner works on. This kind of restoration work includes metal-based art and architecture, from Donald Judd sculptures to the St. Louis Gateway Arch designed by Eero Saarinen, which was analyzed by Zahner field crew last year.

“Zahner also takes on other restoration and engineering projects; last year, Kerry “KB” Butler, the plant’s lead welder, helped perform a core analysis of the stainless-steel-clad Gateway Arch, in St. Louis, to see how it’s holding up.”

Working on the Gateway Arch was especially meaningful for Zahner head welder Kerry Butler, who grew up in the St. Louis area before moving to Kansas City and becoming an employee at Zahner.

Restoration work isn’t always so grand in scale. Zahner provides restoration for a variety of metal applications, including metal sculptures to aging custom metal facade systems, or even classical architectural features on historic buildings.

Recent projects include the cornices for the temple in Nauvoo, Illinois, the dome restoration for the Franklin County Courthouse in Ottawa, Kansas, or the canopy for the Commerce Bank Headquarters in Kansas City, which was critically damaged when a truck backed into it.

In situations like the canopy mentioned above, Zahner will not only repair the metal parts, but also will involve local artists for other aspects. For the canopy, Zahner hired two local artists to create new stained glass and traditional cast aluminum features.

PHOTO © A. ZAHNER COMPANY.

Building in Kansas City’s Silicon Prairie

Towards the end of the article, Capps hints at Zahner’s ShopFloor group. These are the engineers and web technology developers who craft facade and design systems of tomorrow.

“One part of the Zahner plant is essentially a tech firm, where design engineers use custom software to imagine metal surfaces and facades that in many cases have no precedent.”

This part of the Zahner office is known as ShopFloor. Here, engineers develop apps for architects, designers, and artists. Such apps include: a tool that allows users to design furniture generatively; an image-based generator for creating decorative metal screenwalls; as well as R&D for new facade technologies which could end up as apps for ShopFloor.

The Atlantic article ends with Zahner’s flagship product system, a patented technology which makes buildings like the Petersen Museum possible.

Zahner’s central innovation, known as the Zahner Engineered Profiled Panel Systems (ZEPPS), demonstrates how far digitally driven manufacturing has come. Picture two shapes: a cube and a Möbius strip. The cube is straightforward to build, but the latter requires custom components. The ZEPPS process marries digital modeling with fabrication to make such pieces possible. Using this method, Zahner can build something as complex as the Petersen’s winding ribbons —no two panels of which are the same—as easily as if they were being assembled from a kit.

Zahner developed the ZEPPS Technology as a digital tool set to construct complex forms. Examples of its uses include as dual-curved roofs, structural underlayment for curved ceramic facades (or other materials such as glass), and building crown architecture on difficult installations such as skyscrapers, or the curving facade of ribbons which envelops the Petersen Museum.

ZEPPS becomes more efficient with each new iteration. In the future, seeing custom curved roofs and facades may become as commonplace as the rectangular boxes which now permeate our cityscapes.

Read the full story online or in the November, 2015 issue of The Atlantic.