Get Inspiration, Delivered.

Join our newsletter and get inspiring projects, educational resources, and other cool metal stuff, straight to your inbox.

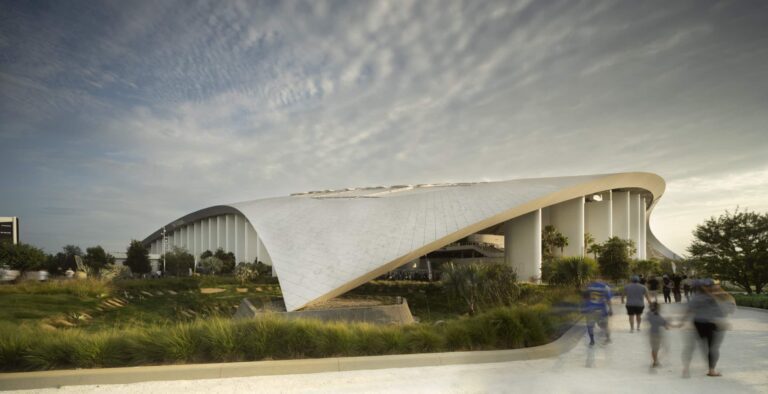

Architect Frank O. Gehry has made a career out of bending vertical and horizontal lines of building construction into something defiant and sometimes poetic. With Seattle’s EMP, opened just over a week before the Fourth of July, he has met his perfect client in Allen and his metaphorical match in rock-‘n’-roll. The resulting architecture is a unique performance and a new landmark on the edge of the Seattle Center.

The new building’s metal skin looks like the shining surface of a jet. Yet it ripples and floats freely, inviting historic references to sculptural drapery from Nike of Samothrace to Claus Sluter’s Fourteenth Century carvings (Gehry’s favorite). Ribbons of translucent “roof sculpture” add another undulating layer.

According to the underspoken Gehry, the real inspiration for the project is a pile of trash he gleaned from an electric guitar shop near his office in Santa Monica. Indeed, the forms and finishes of EMP touch on some potent layers of American subconscious: Fender guitars, auto bodies, and a touch of rental tux.

Defying the traditions of architecture and sculpture, EMP is very much about color tuned to evoke visceral responses. The most striking of the five tones that mark different sections of the building is a deep pastel blue rendered in non-fading auto body paint. That is rivaled by the pulsing red of another section. Three more tones are achieved by specially treating the finish of the metal. They are gold, silver, and a shimmering Purple Haze.

Meeting Yesterday’s Future

EMP’s futuristic bent is right at home in the Seattle Center. Towering next door is the Space Needle, the landmark that dates from the 1962 Worlds Fair. Other futuristic remnants from the past include the Pacific Science Center, the Key Arena (Old Coliseum), and the renovated International Fountain. The carnival lights and year-round rides of the Fun Forest flash and turn just outside the walls.

“The site generated a lot of freedom,” says Gehry.

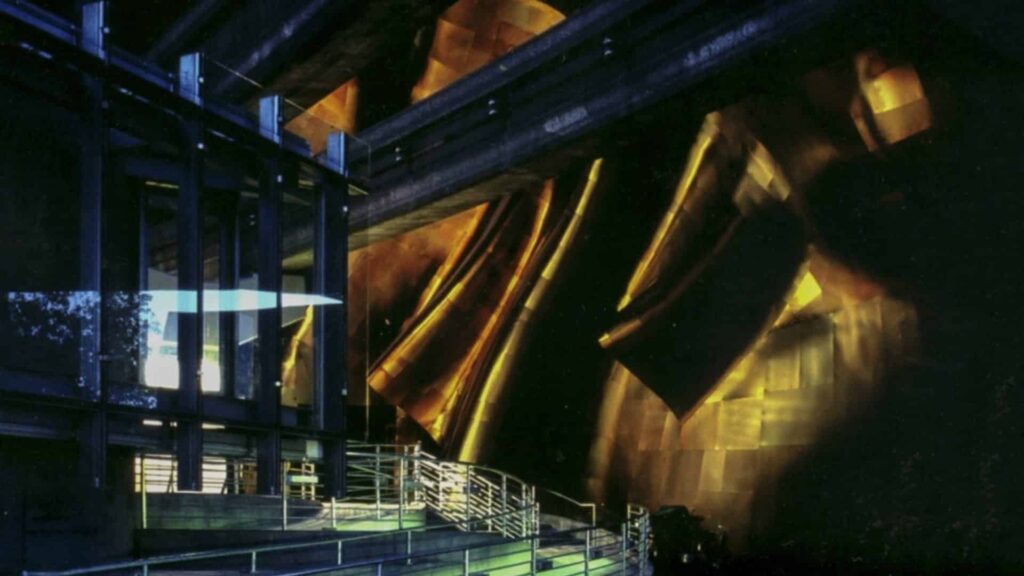

At once industrial and heroic, surreal and ironic, the visual impact of EMP demands strong reactions, and it has reaped a predictable wave of outrage among citizen critics. But once the doors opened, the sour notes were silenced by the play of artifacts and electronic sound and images and by the many-layered interior views and sculptural effects.

Inside the Temple of Rock

The two entrances to the 140,000-square-foot (13,000-square-meter) building, one at the street and a more prominent one on the second level at the edge of the Fun forest, are connected by a grand stairway.

The interior is divided by a multistory “snakewall” wall that dominates views up and down the large stairways and separates the exhibit and educational spaces from support areas.

From the second-level entrance area, visitors enter Sky Church, a stagy, multi-story space dominated by projected imagery. At the far side, an opening reveals a flashing screen and entrance to the Artist’s Journey, a combination documentary and motion platform ride.

The back of Sky Church opens into a wide avenue between temporary and permanent exhibits that beckon like shop fronts. At the end of the street, a linear series of exhibits called Northwest Passage dedicated to traditions and personalities from the Northwest in popular music winds around the outer wall. Up another open stair, the third level of EMP holds Milestones, a collection of artifacts and images commemorating important moments in pop music. Also located on the third level are a series of rooms and nooks with interactive exhibits.

In smaller side galleries, the educational and curatorial mission of the project is supported by tens of thousands of artifacts, from handbills to doodles to stage memorabilia and clothing–and perhaps more guitars than there have ever been in one building. There is a tantalizing display of audio and video recordings, some very obscure and some newly created in the form of interviews of little known artists.

At the heart of Experience Music Project is the spirit of Jimi Hendrix, demigod of rhythm-and-blues, funk, and psychedelic–the local son whose mythic persona and tortured, soaring guitar solos still reverberate around the world. From the Jimi Hendrix Gallery to the exterior “Purple Haze,” the hero lives on in his home town.

Allen and the many creators of EMP understand the intimate relationship between rock-‘n’-roll and electronics. With the exception of a platform thrill ride, thinly based on a funky block party, this project has taken that relationship to a new level. Deep in the center of EMP is an area filled with nooks, crannies, and booths and a simulated recording studio in which people can explore the limits of their instrumental and vocal talent with state-of-the-art enhancement. There’s a booth that can simulate the acoustics of a stadium or a concert hall.

Challenges for Space-Age Software

Although 100 physical models were made for EMP, the building itself was born of advances in software. Molding a design from the outside has become a specialty of Gehry’s firm, and his project teams have developed some unique methods of product delivery. They have appropriated sophisticated 3D modeling software technology for the purpose.

The key is CATIA, developed by the French company, Dassault Systemes, for the design of Mirage fighter jets. CATIA is widely used in aerospace and automotive industries, where structures begin with the precise shaping of the outer shell. One of few architects to use the system, Gehry has exploited its potential to the fullest at EMP.

Electronic modeling was so integral to the design and construction of the project that the paper stage of construction documents was sidestepped. The 21,000 eccentrically shaped metal shingles that form the outer shell were cut by lasers guided by data generated directly from the modeling software.

It’s easy to understand the early negative reactions to EMP’s design by drive-by reviewers. The construction was alternately poetic and ugly, depending on the moment in time and the eye of the beholder. First came the excitement of the snaking I-beams and a hint of the shape to come. The intricate lacing of secondary steel formed the basis for a layer of shotcrete, over which the moisture barrier was painted. Then for a while, the coated structure bristled with shorter pipes that extended out to support the lapped panels of the outer skin.

Equally challenging was the demand for acoustics and sound isolation and the orchestration of the building systems. The exposed structure is an excellent reflector of sound, and the many separate sound sources that threatened to collide have been well absorbed. The collection of 80,000 artifacts, 1,200 on display, require sophisticated climate control at the same time that the openness of the interior leaves no place to hide the mechanical systems. Extraordinary design and detailing have made the concept work.

“No one ever said ‘It can’t be done,’” said Dave Arnold, EMP project manager for LMN Architects, the local architect for the project.

The first crowds have come and gone, and it remains to be seen whether a museum of rock can become a living, growing cultural center and a resource of the future. Seen from outside in the summer dusk, the lighted walls of EMP rise like the folds of a cosmic mushroom. The Monorail comes and goes, the roller coaster dives and loops, and the Space Needle hovers with undiminished authority over it all.

Jimi Hendrix aside, it’s easy to believe that innocence and experience can live on together in Seattle.

About the Author

Clair Enlow is a freelance journalist and civic columnist for the Seattle Daily Journal of Commerce, covering environmental issues, urban design, architectural policy and professional culture. Her byline has appeared in Metropolis, ARCADE, Pacific and Architectural Record magazines and several other arts and design publications. Follow her at @Clair Enlow