Get Inspiration, Delivered.

Join our newsletter and get inspiring projects, educational resources, and other cool metal stuff, straight to your inbox.

This month’s issue of Architectural Record features a story by Beth Broome which describes the genesis of the Eli & Edythe Broad Museum, as well as A. Zahner Company’s role in the design-consulting, manufacturing and providing the installation of the museum’s folded origami metal facade.

The story, which can be read in full on ArchRecord, is excerpted below and includes additional images and video from Zahner.

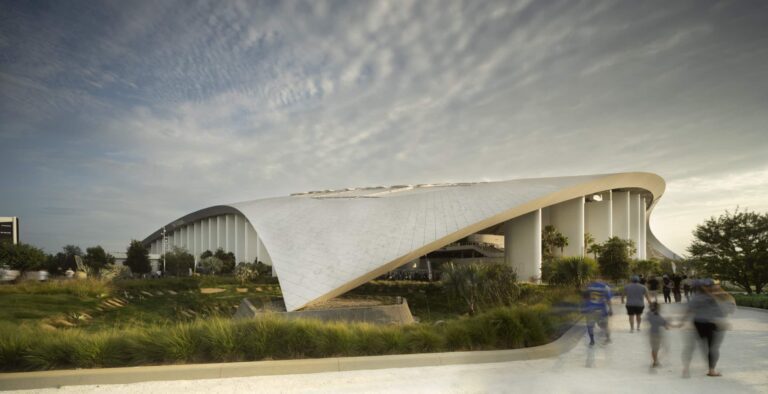

The New Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum on Michigan State University’s East Lansing campus bursts from its traditional collegiate setting like a futuristic concertina pushing free from the deep pit of the devil’s orchestra. “It is a strange object sitting on the edge of campus,” admits Zaha Hadid, but one with a magnetic quality, she points out. “This radically abstract object,” adds her partner Patrik Schumacher, “brings this element of making strange—of building something to be explored and discovered.”

Bold and brassy, the building, say the architects, was designed with some restraint—a result of its strict $45 million budget and modest size of 46,000 square feet. In fact, it is devoid of curvilinearity: All surfaces are flat and all lines, as much as they dart hither and thither, are straight. “We imposed this formal universe of the trapezoidal volumes and spaces all the way through,” says Schumacher. The building’s tilting and thrusting and crazed striations make it appear distorted, and its volume is difficult to understand without a complete tour around its exterior.”

The pleated and louvered metal skin was present in the architects’ first sketches. Motivated by a desire to admit filtered light, the designers mimicked a factory sawtooth roof in miniature and then expanded the idea to characterize the zigzagging of the whole surface. The striations shooting off in all directions are like pinstripes gone wild, which, in concert with the metal’s reflectivity, pleasantly activate the surface. Using a 3-D model, the team—including ZHA in London, IDS outside Detroit, engineers Structural Design Inc. in Ann Arbor, and consultants Zahner in Kansas City, Missouri (for stainless steel), and Josef Gartner in Germany (for glazing and structural steel)—held weekly calls for almost a year to refine the envelope. You get the sense that ZHA conducted this maniacal symphony because it could, cheered on by Broad and MSU, who will use the resulting big gesture as a calling card. Nevertheless, respecting the scale of the neighboring leafy Collegiate Gothic red-brick quads and the commercial strip across the way, the building fits in.

By dispensing with the white-cube gallery, the architects say they hoped to challenge curators and visitors. “We want to participate in the dynamism of the building, rather than try to figure out how we are going to fight this thing,” says museum director Michael Rush. Pointing to parallel ambitions in contemporary art, he underscores the opportunities here: “In a structure like this, where the body is engaged physically with its surroundings, you have this amazing synergy between building, art, body, and perception.”

Read the full story, at ArchRecord, or visit the project’s page on Zahner to learn more about how we developed and completed the project.