10th Anniversary of the New de Young Museum and its Sheet Metal Magic

“Metal runs in the veins of this company.”

A decade ago this month, the new de Young Museum opened in San Francisco, California. The Museum has created a special website to celebrate 10 years of the New de Young. The same month ten years ago, Metropolis Magazine published an eight-page profile on Zahner by Peter Hall entitled Sheet Metal Magicians. Hall is a design writer based in London who immersed himself in the A. Zahner Company factory culture, and discovered how such a building comes together.

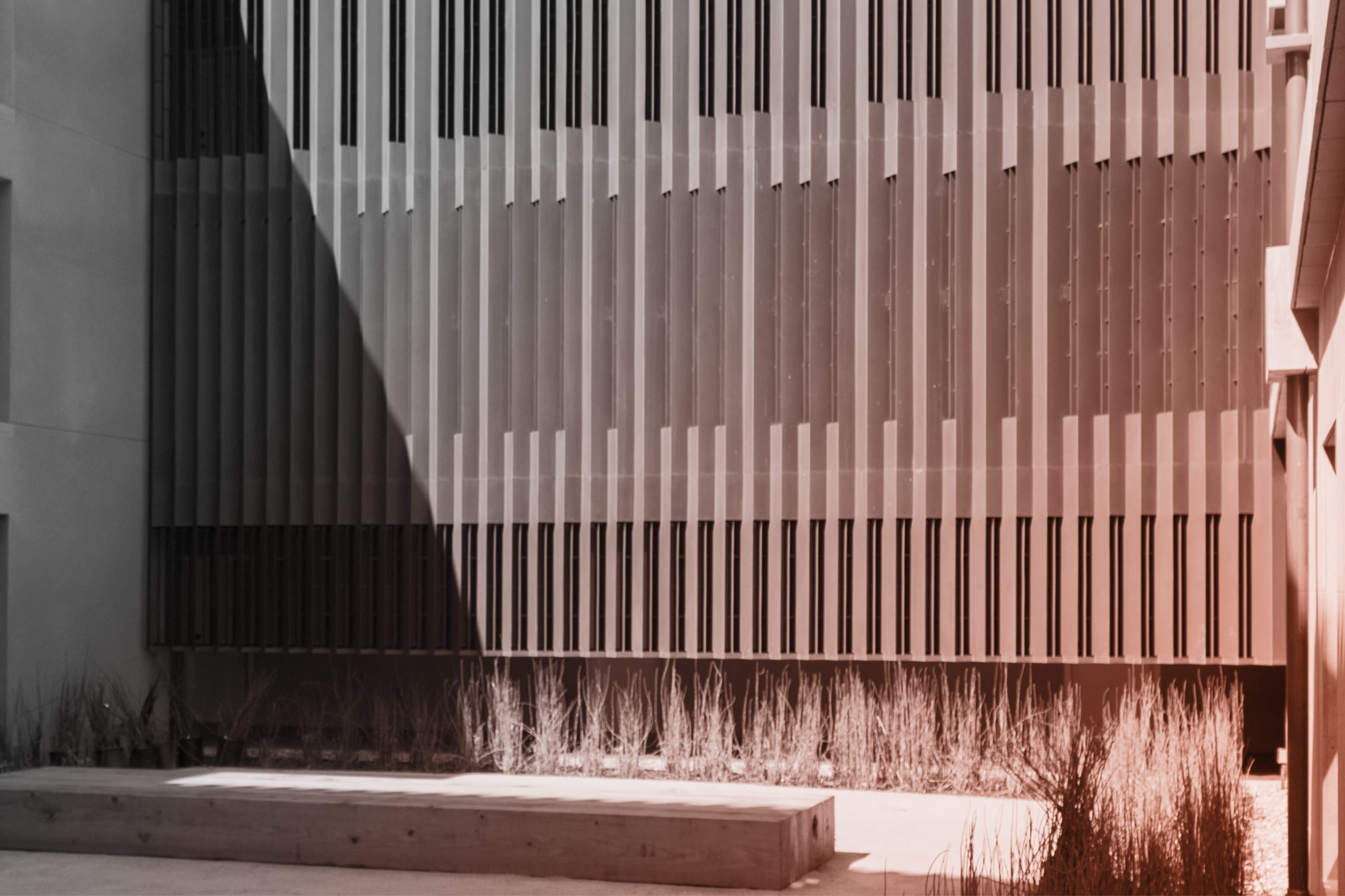

de Young Museum facade during construction.

Photo courtesy of the de Young Museum.

Metropolis Magazine feature by Peter Hall

Courtesy of Metropolis Magazine.

Glass atrium lookout room at de Young.

Photo courtesy of the de Young Museum.

At the time, Zahner was wrapping up construction for the de Young Museum. The building was designed by Herzog & de Meuron with executive architect Fong & Chan, and managed by Swinerton Builders. Zahner was responsible for the entire facade including the metal, glass and twisting structural form. Its metal facade was manufactured in its entirety at the Zahner shop in Kansas City. The story by Hall provides an in-depth look at his experience at Zahner.

“

“Metal runs in the veins of this company.”

Peter HallMetropolis.

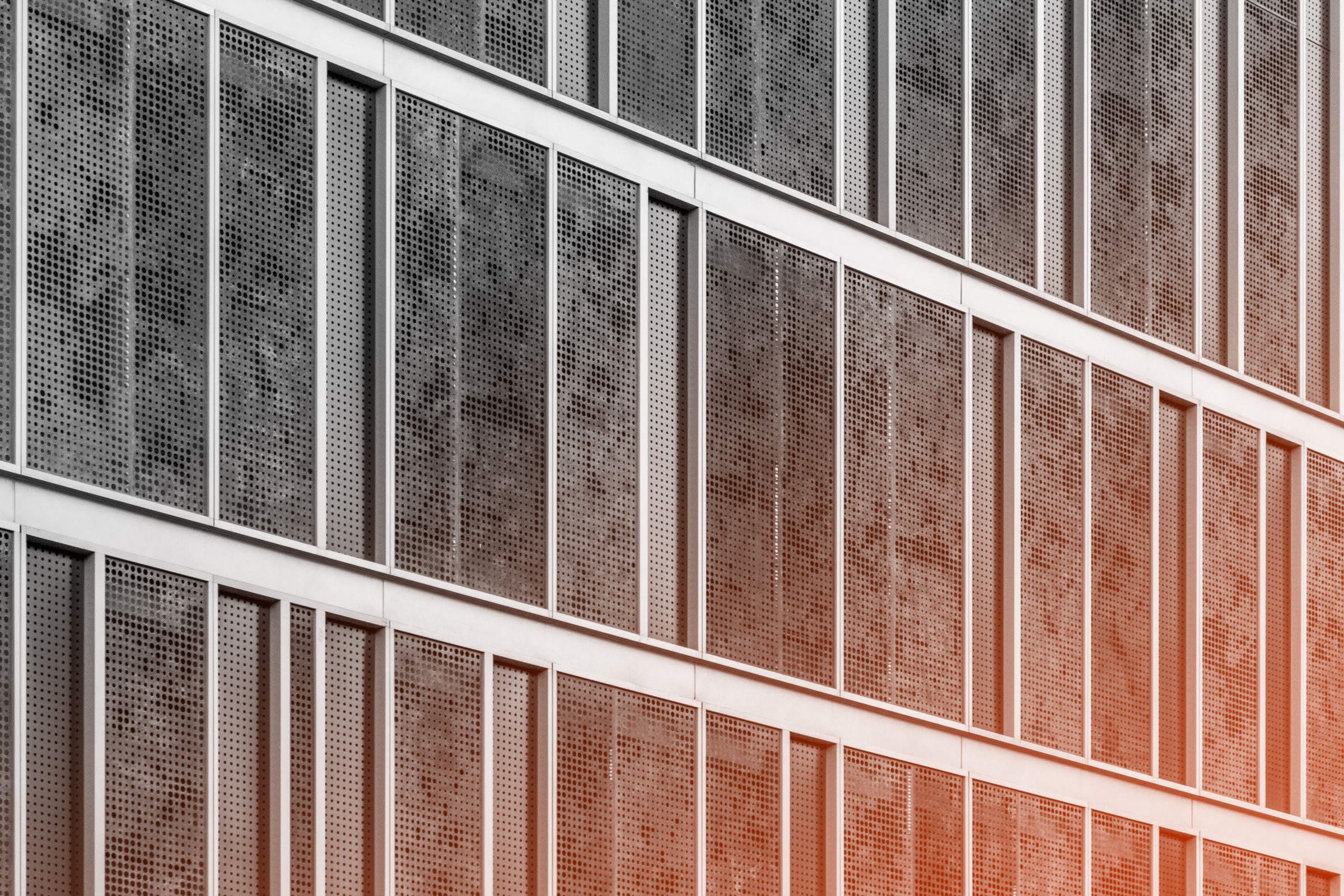

On the walls and lying around on shelves and surfaces are zinc and copper panels, each bearing signs of having undergone tests for different patterns and patinas. Outside, the boxy 1980s structure has become a palimpsest of experimental building skins, the original weathering steel skin in turn covered by copper panels for the de Young.

The panels in Kansas City were a test run for the distinctive facade of the de Young Museum, opening this month in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park. The architects, Herzog & de Meuron, have described it as a metamorphosing permeable skin intended to mimic the effect of light filtering through a canopy of leaves. It is the job of engineers like Paul Martin, at A. Zahner Company, a 108-year-old architectural-metal firm in Kansas City, to turn such flighty metaphors into hard reality.

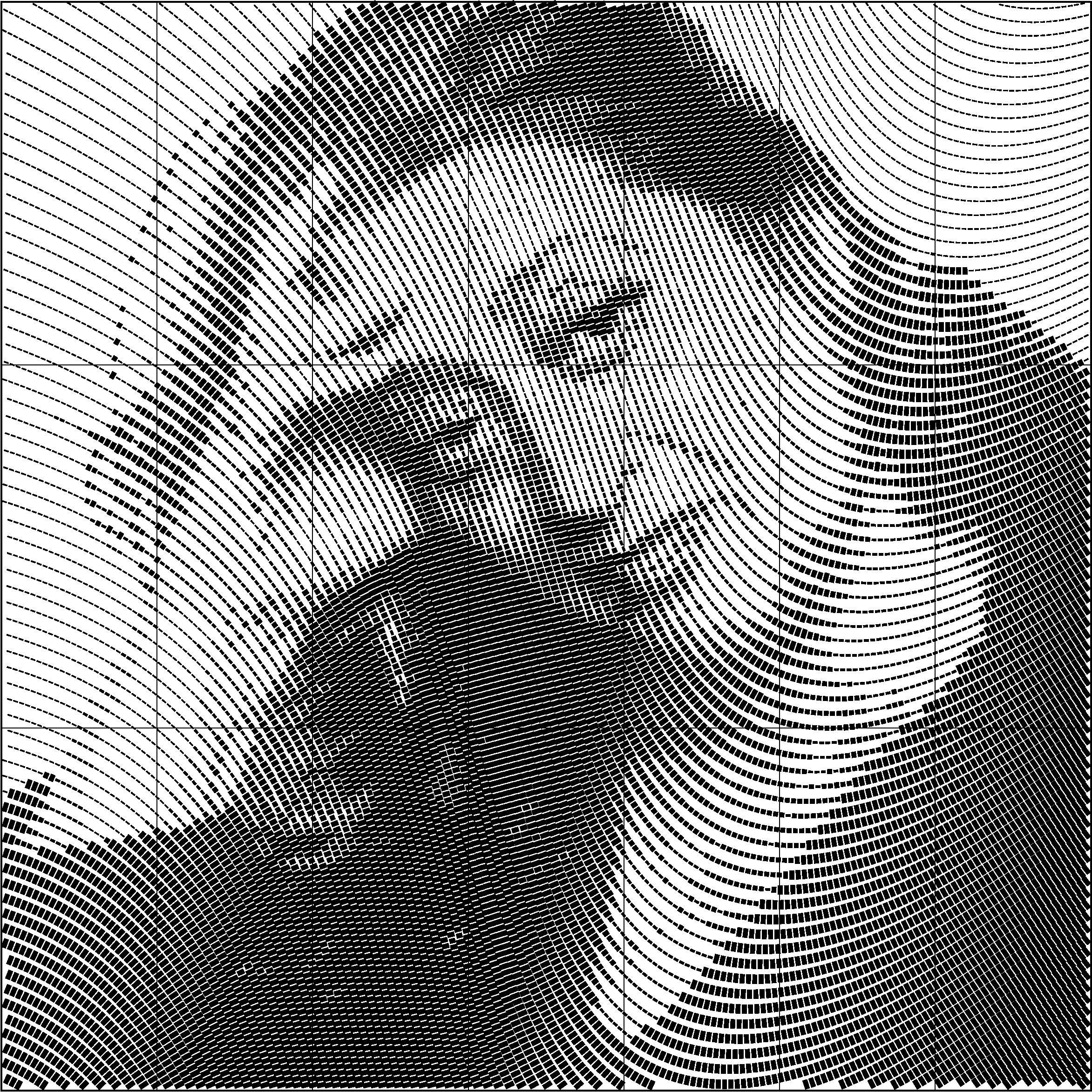

Hall also describes how the pixelated metal surface was created, what would go on to become the patented ZIRA technology, powering both Zahner’s ImageWall product as well as custom perforated metal licensees around the United States.

Developing a satisfactory method for fabricating the de Young facade took the best part of a year. Using a series of abstracted photographs of trees in the park as their source, Herzog & de Meuron architects developed a system with Zahner for replicating the dappled-light effect with embossed concave and convex circles of eleven varying depths and perforated holes of six varying diameters.

Further factory tests using the nibbling machine revealed that putting a flat bottom on the embossed circles increased the contrast at a distance. The challenge for the architects was that the design called for several hundred of these shapes in each of the 7,000 copper panels that made up the building skin.

“In the beginning the process was almost barbaric, with me sitting in front of a computer with AutoCAD manually placing different-size dots,” Herzog & de Meuron architect Chris Haas says. “After weeks of that we realized the amount of time it was consuming.”

Zahner pulled in a programmer, Eric Wilhelm, who wrote software in Perl that acted as a direct interface between architect and machinery. Armed with this automated version, Haas could adjust the contrast and porosity of the facade by changing the pixel density in a Photoshop image.

The Perl script would then spit back a CAD file that could be the basis of the information read by the machines on the factory floor. “In the end they have tags for every panel in the building indicating the elevation and how far the panel was from the edge,” Haas says. “If any part is damaged, Zahner can plug in the file name and repunch it in an instant.”

This rudimentary script was further developed over the years internally at Zahner. In 2014, the script was completely rewritten and developed as the ImageWall, an interactive perforation generator which enables the creation of perforated metal screens with user-uploaded imagery.

Among the challenges of the de Young Museum, the most trying for the entire team may have been the patina process.

Herzog & de Meuron had expected its gleaming penny-colored de Young finish to progressively fade from a bright copper to a cinnamon color and eventually assume a rich green patina that would blend with its park surroundings over a decade or more.

But in foggy San Francisco there was a little too much salt in the air, and a few weeks after the facade was erected dark black blotches began appearing across the perforated forest of metal. Museum trustees freaked out. “A trustee asked how we could avoid this ‘adolescent period,’” Bill Zahner recalls. “I said, ‘You’re just going to have to wait.’”

Waiting proved to be exactly what the Museum’s patina required. Just in time for opening, the Museum’s natural patina evened out into a warm umber. Today, ten years later, the Museum has taken on shades of mulberry violet with hints of turquoise.

Read the full article in Metropolis, and visit the de Young Museum’s special website celebrating the 10-year anniversary of the de Young Museum’s new building.

PHOTO © Tim Hursley

PHOTO © Tim Hursley

PHOTO ©️ Parrish Ruiz de Velasco (parrch.com)

PHOTO ©️ Parrish Ruiz de Velasco (parrch.com)

© Fedora Hat Photography

© Fedora Hat Photography Photo by Andre Sigur | ARKO

Photo by Andre Sigur | ARKO

Ɱ, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license, edited.

Ɱ, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license, edited.