Get Inspiration, Delivered.

Join our newsletter and get inspiring projects, educational resources, and other cool metal stuff, straight to your inbox.

The November issue of Architectural Record featured the Hunter Museum addition in Chattanooga Tennessee. Designed by Randall Stout Architects, the Museum’s surface design includes curvilinear stainless steel forms by Zahner, as well as a custom patina on zinc developed by Zahner.

The November 2005 issue of “Architectural Record” magazine features the Hunter Museum of Art by Randall Stout [pages 122–129] in a section devoted to museum projects around the world. The article by Clifford A. Pearson describes the decision by the Hunter Museum to expand, and how Stout’s transformative vision gave the Museum a prominent outlook over the Tennessee river below.

Stout originally contacted Zahner for the stainless steel clad roof forms because he was familiar with Zahner efforts on various projects for Gehry Partners (Stout was a former protege of Frank Gehry in the 1990’s).

Designing the building envelope system for the Museum presented some unique challenges. The roof elements presented a challenge because they extend out over the river. Further, in addition to being difficult to accurately construct, they would have been expensive to fabricate via conventional stick-built framing in the field.

The architects selected Zahner to manufacture the building’s complex roof and facade system. By using ZEPPS, the Zahner-patented system for building sculptural designs, the team was able to realize these challenging aspects in with efficiency and within budget.

The Arch Record article by Clifford A. Pearson describes the decision by the Hunter Museum to expand, and how Stout’s transformative vision gave the Museum a prominent outlook over the Tennessee river below.

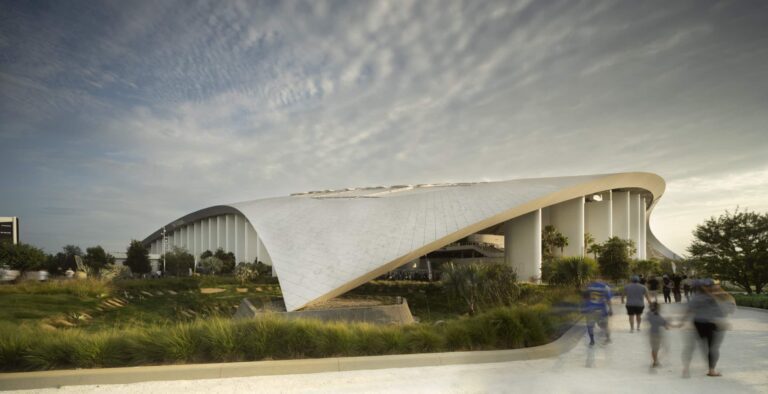

After nearly 50 years of splendid isolation on the bluffs overlooking the Tennessee River, the Hunter Museum decided to reach out to the city beyond its gates. So in 2002, it announced a major expansion that would not only provide 30,000 extra square feet for galleries and special functions, but connect the venerable institution to Chattanooga’s redeveloped waterfront and its resurgent downtown. “We wanted to take the Hunter off the hill,” states Rob Kret, the museum’s director since 2000. In April 2005, a bigger, splashier, and more accessible Hunter, designed by Los Angeles–based Randall Stout, FAIA, opened its doors—literally and figuratively—to a public that included many people who never felt welcomed before.

In the 1970s, the museum had built a Brutalist concrete wing to the east of the mansion and moved its main entrance there. So some people figured the museum would continue expanding in that direction. But Stout proposed adding the new structure to the west, shifting the museum’s focus toward downtown and creating an ensemble of buildings with the mansion at its center. Like a chess player’s first move, the siting of the new 20,000-square-foot building helped shape a long series of decisions affecting everything from the layout of galleries in the existing museum to the location of the loading dock and art storage.

But the chess game didn’t stop there. Randall Stout’s office originally proposed that the Hunter Museum’s cantilevered design would be created using a limestone crafted from local quarries. Due to the growing structural steel costs for its design, the weight of the limestone panels were unfeasible, and the entire design team began brainstorming different solutions.

Zahner’s solution was to look at the custom patinas developed by the CEO in research for his books on architecture. Zahner presented a custom patina process on zinc to emulate the variegated color of the stone, fabricating the zinc panels and shingles to match the shape of the limestone panels that were originally planned. The architects loved it, and continued its surface throughout the museum’s interior walls, ceilings, soffits, and various forms.